3. Prevention of human trafficking, criminality and radicalization

Introduction

Description:

This module explores the interconnected risks of human trafficking, radicalization, and criminality among unaccompanied refugee minors and asylum-seeking youth. It provides a comprehensive overview of the structural, psychological, and social factors that increase vulnerability, with a strong emphasis on prevention and early intervention. Drawing on evidence-based practices, real-world examples, and cross-sectoral strategies, the module equips professionals with knowledge, tools, and approaches to protect refugee youth and support their healthy integration into society.

Aim:

The aim of this module is to deepen participants’ understanding of the factors driving trafficking, criminal exploitation, and radicalization of refugee youth, and to develop the skills and competencies needed to prevent and respond to these challenges through holistic, trauma-informed, and culturally sensitive interventions.

Learning outcomes:

Knowledge

- Define human trafficking, radicalization, and criminality in the context of refugee youth.

- Explain how trauma, social exclusion, and loss of identity contribute to vulnerability.

- Identify the spillover effects of cross-border criminal networks.

- Recognize early signs of exploitation and radicalization.

- Apply practical prevention and intervention tools, including trauma-informed care, mentorship, and cross-sector cooperation.

- Communicate effectively and sensitively with refugee youth and their families.

- Design and deliver culturally adapted prevention programs.

- Build trust and safe spaces that foster belonging and resilience.

- Collaborate with stakeholders across sectors to address root causes and protect at-risk youth.

Human trafficking, radicalization and criminal risk among refugee youth

The interconnected risks facing refugee youth:

Unaccompanied refugee minors and asylum-seeking youth face overlapping dangers that go far beyond their immediate need for safety and shelter. Human trafficking, radicalization, and involvement in criminal networks are not isolated problems—they are interconnected risks that often reinforce each other.

Human trafficking exploits the extreme vulnerability of children and youth on the move. Many refugee youth lack stable caregivers, legal protection, and financial resources, making them easy targets for traffickers who promise safety, work, or belonging. Once under the control of traffickers, young people may be forced into sexual exploitation, forced labor, or criminal activities.

Radicalization can also take hold in this context of instability and trauma. Some extremist groups deliberately target marginalized refugee youth, offering a sense of identity, purpose, and community that they have lost. Young people who experience discrimination, isolation, or violence are more susceptible to extremist narratives that frame criminal or violent acts as justified resistance or as a path to dignity.

Involvement in criminal networks is often both a cause and consequence of trafficking and radicalization. Organized crime groups—including gangs and smuggling rings—exploit refugee minors by:

- Using them to transport drugs or weapons across borders

- Forced labor

- Pressuring them to recruit other vulnerable peers

- Forcing them to commit theft, fraud, or violence as a form of debt repayment or initiation

- Exposing them to extremist ideology that blurs the line between crime and political violence.

Using them to transport drugs or weapons across borders

Forced labor

Pressuring them to recruit other vulnerable peers

Forcing them to commit theft, fraud, or violence as a form of debt repayment or initiation

Exposing them to extremist ideology that blurs the line between crime and political violence.

These risks are mutually reinforcing:

- A young person trafficked for forced labor may also be exposed to radical ideology.

- A youth involved in criminal activity may be blackmailed or threatened into deeper exploitation.

Experiences of racism and exclusion fuel feelings of hopelessness, increasing the appeal of both gangs and extremist groups.

A young person trafficked for forced labor may also be exposed to radical ideology.

A youth involved in criminal activity may be blackmailed or threatened into deeper exploitation.

Experiences of racism and exclusion fuel feelings of hopelessness, increasing the appeal of both gangs and extremist groups

Understanding these connections is critical. Effective prevention and intervention must recognize that trafficking, radicalization, and criminal exploitation often stem from the same root causes: trauma, displacement, poverty, isolation, and discrimination.

When working with refugee youth, professionals must address these intertwined threats holistically protecting children from exploitation while also promoting trust, belonging, and positive alternatives.

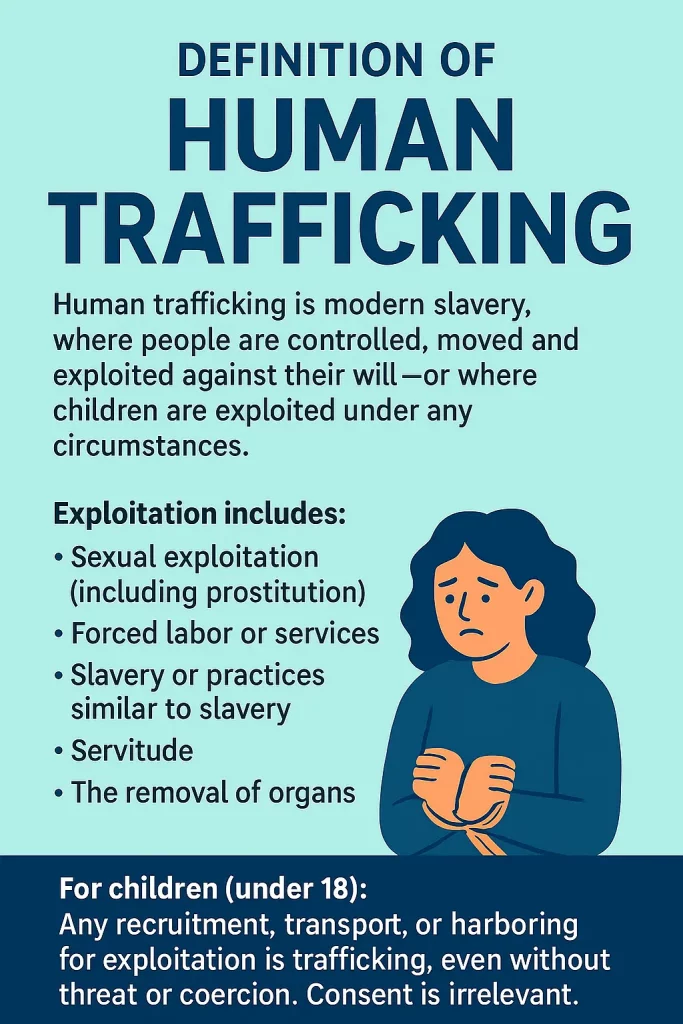

Definition of Human trafficking

The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons, by means of threat, use of force or other forms of coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power or a position of vulnerability, or giving or receiving payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. For more information please take a look at the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime | OHCHR

Organized smuggling networks and refugee minors

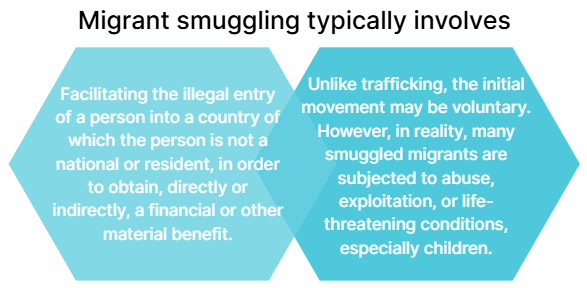

In addition to trafficking, there is a growing problem of organized criminal groups who smuggle migrants, often at extreme risk to the migrants themselves and with enormous profit for the offenders. While migrant smuggling and trafficking are legally distinct, in practice, they frequently overlap—especially for unaccompanied refugee minors.

What is Migrant Smuggling?

Migrant smuggling typically involves | |

|---|---|

Facilitating the illegal entry of a person into a country of which the person is not a national or resident, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit. | Unlike trafficking, the initial movement may be voluntary. However, in reality, many smuggled migrants are subjected to abuse, exploitation, or life-threatening conditions, especially children. |

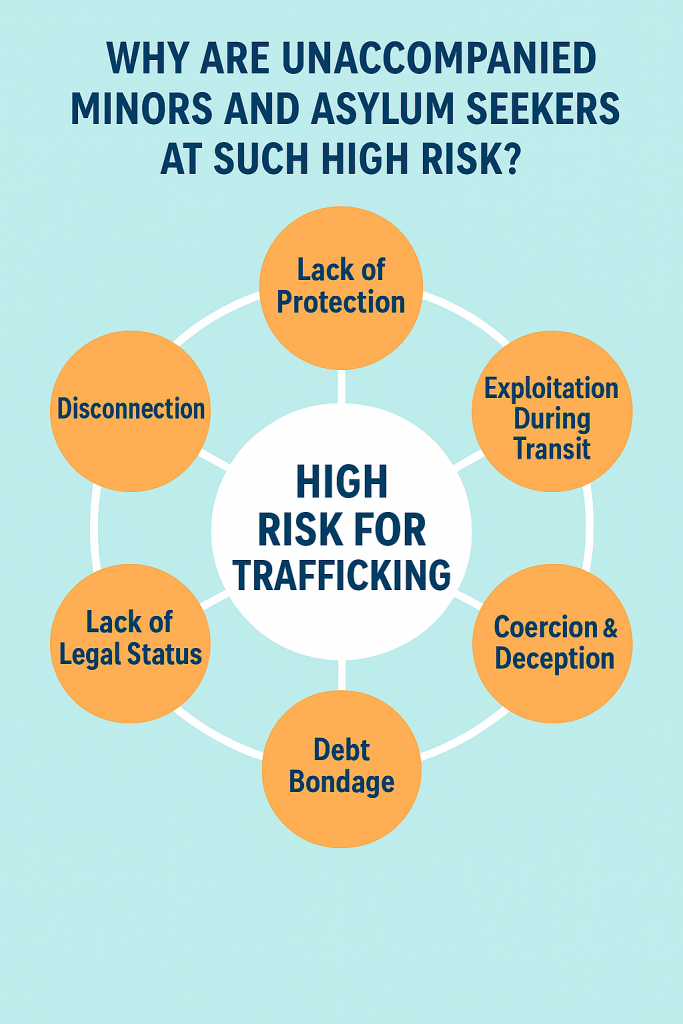

High Trafficking Risks for Unaccompanied Youth

Why Unaccompanied Minors and Asylum Seekers Are at High Risk of Trafficking? | |

|---|---|

Lack of Protection | Traveling alone with no adults to advocate for safety; reliance on smugglers creates vulnerability. |

Exploitation During Transit | Smuggling often turns into trafficking; children may be sold, forced into sexual abuse, begging, or labor. |

Coercion & Deception | Smugglers promise safety but instead use violence, threats, or extortion to exploit children. |

Debt Bondage | Families pay large sums for passage; children feel forced to repay through exploitative work. |

Lack of Legal Status | Without valid documents, children fear authorities; traffickers exploit this fear of deportation. |

Disconnection | Separation from family and community leaves children isolated and without support. |

Examples of Risks Specific to Unaccompanied Minors:

- Being forced to work in sweatshops or illegal cannabis farms to pay off smuggling debts.

- Being sexually exploited in exchange for food, shelter, or onward travel.

- Being coerced to commit crimes such as theft, drug distribution, or document fraud.

- Being held in transit camps under armed guard until families pay ransoms.

For Professionals Working with Refugee Children

Why Does This Matters for Professionals Working with Refugee Children?

Unaccompanied minors are not simply “migrants in transit.” They are among the most at-risk children in the world, targeted by organized criminal groups operating across borders.

Key Implications for Practitioners:

- Never assume a child’s movement was fully voluntary, even if they appear to have agreed.

- Always assess for indicators of trafficking and exploitation.

- Understand that smuggling networks may continue to exert control over minors long after arrival.

- Recognize that fear of authorities can prevent disclosure—safe environments and trust-building are essential.

Never assume a child’s movement was fully voluntary, even if they appear to have agreed.

Always assess for indicators of trafficking and exploitation.

Understand that smuggling networks may continue to exert control over minors long after arrival.

Recognize that fear of authorities can prevent disclosure—safe environments and trust-building are essential.

Radicalization:

Radicalization processes can be characterized by ideology, politics, or religion.

Radicalization involves individuals gradually distancing themselves from society’s democratic principles while simultaneously justifying the use of threats and violence to achieve their goals. Violence committed with ideological, religious, or political objectives is referred to as violent extremism.

Radicalization: A profound process

Radicalization is a dynamic and often gradual process in which individuals embrace radical ideologies. This can include political, social, or religious beliefs that run counter to what is considered acceptable within society. The process usually involves several stages, including exposure to radical ideas, acceptance of these ideas as part of one’s identity, and ultimately mobilization to action. Along the way, the person may be subjected to greater or lesser degrees of pressure and influence from individuals and environments. For some, the process results in planned or impulsive action, while others will stop or turn back along the way.

Violent Extremism: The Transition to Action

Violent extremism represents the most severe stage of radicalization, where individuals or groups move from embracing radical ideas to carrying out acts of violence. This can include terrorist attacks, violence against individuals, or attempts to destabilize society. The motivation behind violent extremism can vary, ranging from political or religious agendas to revenge or the perception of a threat to one’s identity. The connection between radicalization and violent extremism is complex and diverse, depending on context and individual factors. Knowledge about the pathway into radicalization is important, both for prevention and for helping people disengage.

Characteristics of Radicalization Processes

- Variation in Time and Content

Radicalization processes vary in both duration and content. Some individuals spend years and never commit violence, while others may engage in extremist violence after just weeks or months. Do not wait and see. Explore and share your concerns.

- Offering a Solution

The search for social belonging, identity, meaning, and protection are central factors and drivers at the start of many radicalization processes.

- Radicalizers as Drivers

Contact with a radicalizer, who motivates or invites someone into an extremist community, can further accelerate the radicalization process. The person and the message he or she conveys can create a sense of belonging, security, and purpose. There may be varying degrees of pressure or persuasion. Some processes are initiated when one or more radicalizers make contact, “groom,” or in other ways invite someone into a community. The beginning of the process may be characterized by voluntariness and independence, but this can gradually be replaced by coercion, threats, or demands for loyalty.

- Grooming Process

Grooming in radicalization refers to a deliberate and systematic effort by a radicalizer to build trust and emotional connection with an individual over time, with the aim of influencing their beliefs and behaviors. The process often begins with seemingly benign interactions—offering friendship, support, or understanding of personal struggles. Gradually, the radicalizer introduces extremist ideas and narratives, framing them as solutions to the person’s problems or as a way to achieve purpose and belonging. As trust deepens, the individual may be isolated from alternative perspectives and increasingly dependent on the radicalizer for validation and identity. This manipulation can escalate to demands for loyalty, participation in illegal activities, or the acceptance of violence as justified.

- Radicalization Online

A radicalization process does not depend on physical meetings. Radicalization can occur online, on social media, and in chat rooms. Online relationships can be just as significant as physical friendships and should therefore be regarded as equally important.

- The Process Is Not Linear

There can be periods when doubt makes the person uncertain. In other periods, the process escalates and conviction is strong. Our influence is always greatest at the start of the process and when the person is experiencing doubt and uncertainty.

Criminality

Criminality is the state or quality of engaging in behavior that violates the law. It refers to the commission of acts that are defined as crimes by legal systems, encompassing everything from minor offenses to serious and organized crime. More simply put, criminality is the pattern or tendency of committing unlawful acts.

Criminality refers to behaviors and actions by young people that break the law. This can include a wide range of illegal activities, from minor offenses like vandalism, theft, or underage drinking, to more serious crimes such as assault, robbery, or gang-related violence.

In a youth context, criminality is often shaped by factors such as peer pressure, lack of positive role models, difficult family circumstances, social exclusion, or the search for identity and belonging. Early involvement in criminal behavior can increase the risk of repeated offending and deeper involvement in criminal environments.

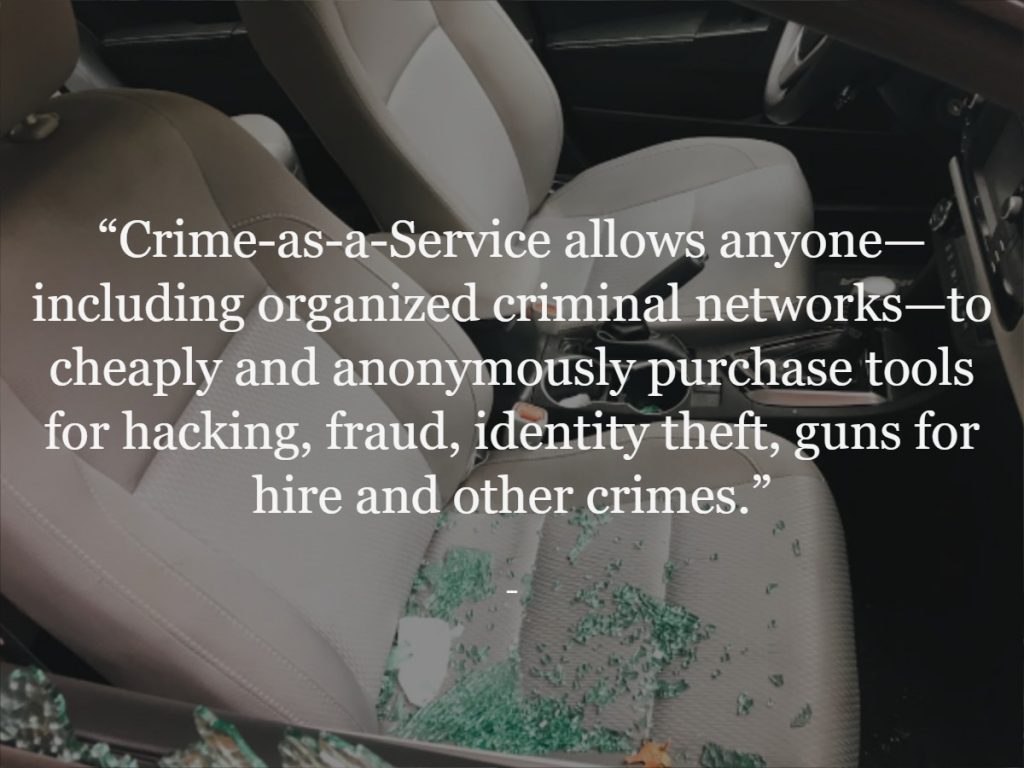

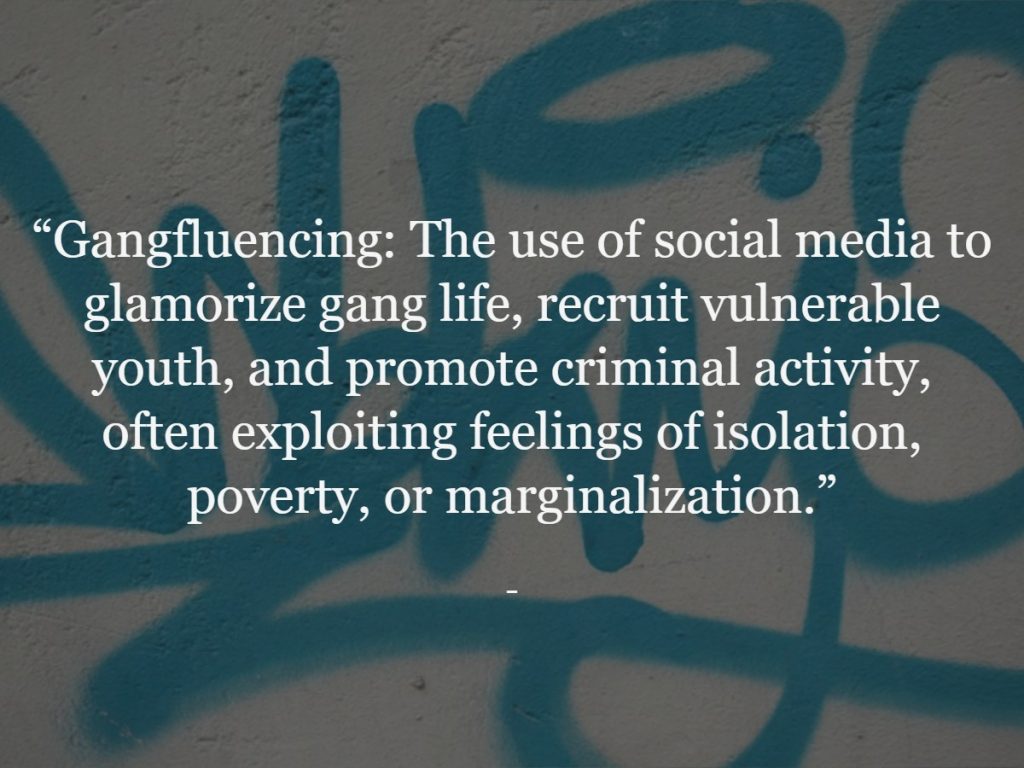

Crime-as-a-Service and gangfluencing are particularly significant threats to unaccompanied refugee minors and asylum seekers because they combine global reach, accessibility, and anonymity, making it easier than ever for criminal groups to target vulnerable young people.

Crime-as-a-Service allows anyone—including organized criminal networks—to cheaply and anonymously purchase tools for hacking, fraud, identity theft, guns for hire and other crimes. This lowers the barrier to entry for illegal activities and creates new opportunities to exploit refugee youth, either by involving them directly or by stealing their personal data.

Gangfluencing leverages the power of social media to glamorize gang culture, recruit new members, intimidate rivals, and promote criminal lifestyles. Refugee youth, who often face isolation, discrimination, and poverty, are especially susceptible to this digital grooming. Gangs use platforms like TikTok and Instagram to offer a sense of belonging, fast money, and status—drawing young people into exploitation and criminality.

Together, these trends make it easier to:

- Target, contact, and manipulate minors remotely across borders.

- Exploit their vulnerabilities, including trauma, loneliness, and lack of protection.

- Scale criminal operations quickly, with little risk of detection.

For professionals working with refugee youth, recognizing these dynamics is essential. Addressing the risks requires not only law enforcement responses but also prevention, education, and strong support networks to counter the pull of criminal influence online.

Implications | |

|---|---|

Law Enforcement Challenges | Gangfluencing and Crime-as-a-Service (CaaS) presents new challenges for law enforcement, as it blurs the lines between online and offline criminal activities. Monitoring and intervening in these activities require sophisticated tools and strategies. |

Community Impact | The influence of gang culture on social media can contribute to the spread of violence and crime in communities, making it harder to combat gang-related issues at the local level. |

Need for Prevention Programs | Addressing gangfluencing and Crime-as-a-Service involves creating prevention programs that educate young people about the dangers of gang involvement and offer positive alternatives to the appeal of gang culture. Training critical thinking skills is an essential part of these efforts |

In essence, gangfluencing and Crime-as-a-Service is the digital evolution of traditional gang activities, leveraging the power of social media to extend the reach and influence of criminal organizations.

Spillover Effects and Unaccompanied Minors

Spillover effects in cross-border crime mean that criminal activities in one country often spread to others. When law enforcement cracks down on gangs, traffickers, or extremist networks in one area, these groups may simply move operations across the border to places with weaker controls.

This affects unaccompanied minors in particular ways:

- Human trafficking networks often relocate, increasing the risk that children will be exploited in transit or after arrival.

- Drug trafficking and smuggling routes shift to new regions, where minors may be recruited to transport goods or repay debts.

- Extremist groups export ideology and recruitment tactics, using online platforms to target isolated young people across countries.There is also the risk that a young person who has been radicalized or recruited in one country may later arrive elsewhere as a refugee. This can unintentionally introduce extremist ideology into new communities and create additional challenges for prevention and integration efforts.

Because unaccompanied minors often lack protection, these spillover effects can quickly lead to exploitation, criminal involvement, or radicalization. This is why cross-border cooperation and early identification are essential to keep young people safe.

Key Takeaway & Examples

- Key Takeaway

The spillover effect in cross-border criminality underscores the importance of international cooperation in law enforcement. Addressing crime in one country often requires coordinated efforts across borders to prevent criminals from simply relocating their activities and spreading the negative effects to other regions.

- Real-life examples:

Example 1

The local Norwegian police have raised concerns about the increasing involvement of young people in criminal networks, a trend that appears to be inspired by or directly linked to Swedish criminal organizations, often referred to as “Svenske tilstander” (Swedish conditions). This development is particularly alarming given Norway’s proximity to Sweden, where these criminal networks are already established and actively operating within Norwegian borders.

In response to this worrying trend, Norwegian authorities are considering closer cooperation with their Swedish counterparts. This includes the possibility of joint patrols between Norwegian and Swedish police forces to combat the rising cross-border criminality. The aim is to prevent the situation in Norway from deteriorating to the levels seen in Sweden and to curtail the influence of Swedish criminal networks on Norwegian soil.

The Spreading of the “Swedish Condition” – Gang Violence and Worries Among its Nordic Neighbours

Example 2

A municipality resettled an unaccompanied minor who had arrived as a refugee from a conflict zone. Unknown to local authorities, the youth had already been recruited by an extremist group before leaving his home country. After arrival, he began trying to contact like-minded individuals and share radical materials online. Thanks to close monitoring and intelligence sharing, the national security services identified the risk early and intervened before a violent act was committed.

Refugee Youth at Risk: Radicalization & Crime

Belonging and Integration

Belonging is a fundamental human need. For young people, especially those forced to flee their homes, participation in social and cultural activities is essential for developing trust, self-esteem, and mutual understanding. Early relationships help build language skills, embrace shared values, and form connections with peers and authorities. When these relationships are missing, children and youth can feel excluded and isolated, which often leads to loneliness, mental health challenges, and passivity.

Unaccompanied refugee and migrant youth frequently face legal, social, and emotional exclusion. They may experience invisibility, isolation, and constant “othering.” If these feelings are not addressed, they can turn into frustration, mistrust, or a sense of disconnection from society. Over time, this disconnection increases the risk of an identity crisis and makes young people easier targets for radical and criminal groups who promise belonging and purpose.

An identity crisis often arises when individuals struggle to reconcile how they see themselves with how society perceives them. For refugee youth, this conflict can be intensified by discrimination, particularly in areas like education and the job market. Repeated rejection because of an ethnic-sounding name or a perceived foreign background can lead to feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt. Over time, they may internalize negative stereotypes, feel excluded from the wider community, and lose trust in institutions.

Social exclusion—such as barriers to education, stable housing, or healthcare—further deepens this sense of isolation. Youth who are pushed to the margins of society often feel they have no future and no place to belong. This creates fertile ground for radical or criminal networks to step in, offering a sense of identity, respect, money, or revenge.

Alongside social exclusion and discrimination, refugee youth often carry deep emotional wounds. Many have experienced war, violence, torture, or the loss of loved ones. Trauma can leave lasting scars, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression. Without proper mental health care, these young people may struggle to regulate their emotions or cope with overwhelming feelings of sadness, fear, or helplessness. This can lead to aggressive behavior, substance use, or withdrawal. For some, the promise of control, purpose, or relief—even through violence or extremism—can be powerfully attractive.

Grief is another powerful factor. Many youth have lost family, friends, homes, and a sense of safety. In the chaos of displacement, there is often no time or support to process this loss. Grief that is unacknowledged or suppressed can turn into hopelessness, rage, or numbness. Radical groups exploit these emotions, using messages like, “They took everything from you—now you can fight back.”

All these factors—trauma, identity loss, social exclusion, unresolved grief—are deeply interconnected and can reinforce each other. Trauma can lead to withdrawal, which deepens isolation and confusion about identity, creating more vulnerability to manipulation and recruitment.

For example:

Trauma causes withdrawal → which worsens isolation → which deepens identity confusion → which makes youth more open to radical influences.

This is why early, culturally sensitive support is not optional—it is essential. Helping refugee youth heal, rebuild their sense of self, and find meaningful connections is the most effective way to prevent the spiral into radicalization and criminality.

Prevention strategies, tools and approaches for practitioners

- Cultural Adaptation of Prevention and Support Strategies

Why does cultural adaptation matter?

Refugee youth and families come from diverse cultural, religious, and linguistic backgrounds. Their experiences, beliefs, and values shape how they understand:

🧠 Mental health and trauma

🤝 Authority and trust

👨👩👧 Gender roles and family obligations

👫 Ideas of belonging and community

🆘 Attitudes toward help-seeking

Without cultural adaptation, well-intentioned support can feel irrelevant, confusing, or even disrespectful. Effective prevention and intervention must align with cultural realities to build trust and engagement.

🛠️ Key Principles for Culturally Adapted Interventions

✅ 1. Respect Different Understandings of Mental Health

- In some cultures, trauma and distress are expressed as physical symptoms (“my heart is heavy,” “my body is tired”) rather than emotional labels.

- Families may see mental health struggles as a source of shame or a spiritual issue rather than a psychological one.

- Strategy: Use culturally relevant language and metaphors. Consider including cultural mediators or interpreters familiar with both the host and origin cultures.

✅ 2. Engage Families and Communities

- Some cultures value collective decision-making over individual autonomy.

- Involving family members and respected community figures can build acceptance and reduce stigma.

- Strategy: When appropriate, integrate family counseling, community consultations, or faith-based partners to reinforce messages of support.

✅ 3. Adapt Intervention Content and Delivery

- Tools like psychoeducation, therapy, or group discussions must be adapted for cultural norms around disclosure, gender dynamics, and hierarchy.

- Strategy: Use flexible approaches, such as storytelling, art, or culturally familiar practices, instead of expecting youth to share personal feelings in unfamiliar formats.

✅ 4. Be Aware of Power Dynamics

- Experiences of persecution and discrimination may lead some youth and families to mistrust authorities or institutions.

- Strategy: Build relationships slowly, emphasize confidentiality, and clearly explain the purpose of interventions to reduce fear.

✅ 5. Train Staff in Cultural Competence

- Staff need skills to recognize cultural differences without stereotyping.

- Strategy: Provide training on intercultural communication, bias awareness, and the cultural context of the populations served.

Understanding the link: Mental health, Radicalization and Criminality

As we mentioned before , there is a strong connection between mental health issues and a young person’s vulnerability to radicalization and criminal behavior. This does not mean that people with mental health problems are violent, but that untreated psychological distress, combined with difficult life circumstances, can increase the risk of harmful influences taking hold. There is a well-documented and complex connection between mental health challenges, such as trauma, depression, anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and a young person’s increased vulnerability to radicalization and involvement in criminal behavior. This connection does not imply that individuals with mental health issues are inherently violent or dangerous, but rather it highlights how untreated psychological distress, when combined with external risk factors such as social exclusion, discrimination, poverty or exposure to violence, can create a fertile ground for harmful ideologies or criminal influences to take root. In such cases, emotional pain, identity confusion and a lack of supportive structures can lead young people to seek belonging, purpose, or a sense of control in groups or behaviors that offer quick but dangerous solutions.

Mental health as a risk factor

Refugee youth often experience trauma from war, violence or loss. They often suffer from depression, anxiety and PTSD. Feelings of hopelessness, worthlessness or isolation are also common for them and when these mental health issues go unrecognized or untreated, youth may act out through violence, theft or drug use (criminality). Or seek belonging, identity or revenge through extremist groups (radicalization).

Psychological vulnerability

Mental health struggles can affect how a young person sees the world, regulates emotions and relates to others. Radical and criminal groups often take advantage of these vulnerabilities. They offer to them a clear identity (“You are a warrior!”; “You matter!”), a cause to give meaning to their suffering or even a group or “family” that accepts them.

Coping with pain the wrong way

Without healthy ways to cope with trauma or emotional pain, youth may turn to violence, substance use and gangs or extremist groups (for protection or belonging). These are maladaptive coping strategies, they feel helpful in the short term, but are dangerous in the long term.

Social and environmental triggers

Mental health problems don’t lead to crime or radical beliefs by themselves. But when combined with discrimination or racism, poverty or exclusion and lack of support or purpose…the risk increases. This means the environment matters as much as the individual’s mental health. Mental

health challenges, especially trauma and identity loss, create emotional and psychological gaps. Radical or criminal groups offer to fill those gaps with false solutions and that is why a prevention must include early mental health care, emotional support and safe spaces for youth to heal, connect and find meaning in positive ways.

Mental health-focused prevention strategies

Mental health-focused prevention strategies

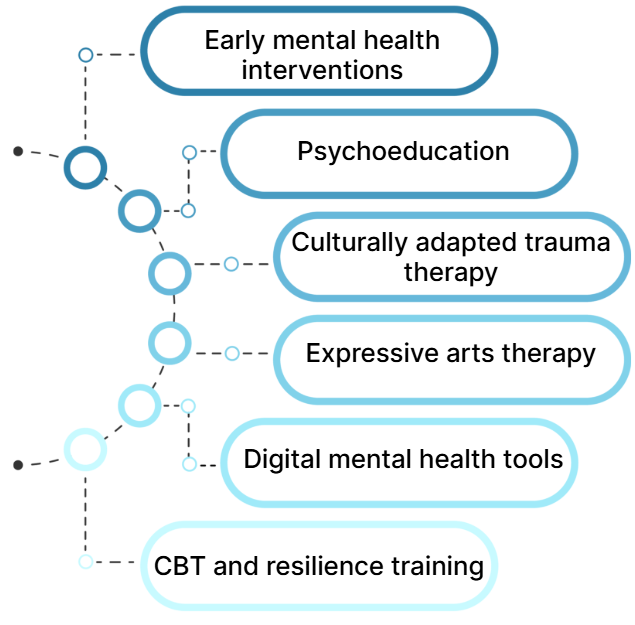

Addressing the mental health needs of refugee youth is one of the most effective ways to prevent radicalization and criminal behavior. When emotional distress is recognized early and treated with care, it reduces the risk of youth turning to harmful groups or behaviors to cope. Below are five key pillars of prevention that focus specifically on mental health, drawn from both evidence-based practice and real-life experience.

6. SECTORS VERSION

Early mental health interventions

Early identification and support are crucial. Many refugee youth carry deep emotional wounds from war, displacement or loss, but these often go unnoticed or untreated. Mental health screening should be introduced during intake processes, such as when a child registers for school, joins a youth center or enters a new community. These screenings can detect signs of trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety or emotional numbness. Psychological First Aid (PFA), especially when delivered in a culturally sensitive and trauma-informed way, can offer immediate emotional support. Trained staff in schools, refugee shelters or community organizations can help stabilize emotional distress and connect youth to further care if needed. Trauma-informed care emphasizes safety, trust and empowerment, ensuring that young people feel secure and respected during every step of the support process.

Psychoeducation

Many youth and families come from cultures where mental health is stigmatized or misunderstood. Psychoeducation helps to raise awareness and build emotional literacy, both of which are vital for early prevention. Teaching refugee youth about how trauma affects the brain and emotions, what healthy coping strategies look like and how to recognize signs of distress in themselves or others helps them take control of their emotional wellbeing. Families also need psychoeducation to understand their children’s behavior and to support them effectively. When parents learn that emotional reactions like anger or withdrawal may be signs of trauma, not bad behavior, they can respond with more compassion. Reducing stigma is key. When youth and families begin to see mental health support as a normal, positive and empowering process, they are more likely to seek help early, before problems escalate into dangerous behaviors.

Culturally adapted trauma therapy

Many refugee youth have lived through war, violence and displacement. These experiences often result in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and emotional numbing. Traditional therapy approaches may not always feel safe or relevant to them, especially when cultural beliefs and communication styles differ. One widely used method is Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET), which is specifically designed for individuals who have experienced multiple traumatic events. This approach guides young people through the telling of their life story, both positive and traumatic events in a structured, safe way. By helping them place traumatic experiences into a coherent timeline, NET allows youth to begin integrating their memories rather than being haunted by them. It restores a sense of continuity and meaning in their lives and has proven especially helpful for war-affected populations.

Expressive arts therapy

For many youth, especially those with language barriers or deep emotional wounds, talk therapy may not be the most effective starting point. Expressive arts therapy offers alternative ways to process pain, release emotions and build identity without requiring verbal explanations. Art forms such as dance, music, drama, painting and storytelling give young people tools to express feelings they may not yet understand or be ready to speak about. These creative methods help reduce anxiety, improve mood and develop emotional self-awareness. They also create a space for joy, imagination, and hope, all vital parts of recovery and growth. When integrated into group settings, expressive arts activities can also strengthen social bonds and foster a shared sense of belonging, helping to rebuild trust and connection after trauma.

Digital mental health tools

As many refugee youth are digitally connected, online mental health tools and apps can be powerful supplements to in-person support. These platforms offer discreet, immediate access to psychological resources and can help normalize conversations about mental health. Apps like MindShift (focused on anxiety), Woebot (a chatbot using evidence-based techniques) or Headspace (mindfulness and relaxation) provide interactive and culturally neutral tools for managing stress, learning coping skills and building emotional awareness. In addition, digital storytelling platforms allow young people to create and share their own narratives through video, audio, or writing. This gives them an active role in countering negative or radical messages online and reinforces a strong, positive sense of identity. These tools promote self-expression, critical thinking and connection with others who may share similar journeys.

Safe and inclusive spaces

Refugee youth need safe spaces where they feel welcome, respected and valued. These environments support emotional healing and reduce the feeling of alienation that often leads young people toward extremist or criminal groups. Community centers, youth hubs or school-based programs should offer structured, positive activities in a nonjudgmental and inclusive environment. Activities might include art, sports, dialogue groups or collaborative community projects. Integration programs that bring together refugee and local youth help foster friendships, mutual understanding and a shared sense of belonging. This reduces social isolation and builds positive identity, both protective factors against radicalization.

CBT and resilience training

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a widely recognized method for helping individuals recognize and change harmful patterns in their thoughts, feelings and behaviors. For refugee youth, CBT can be especially effective in addressing:

- Cognitive distortions (“I am worthless” or “Everyone is against me”)

- Anger management and impulsive reactions

- Feelings of hopelessness or revenge linked to past trauma or injustice

Group-based resilience training workshops complement CBT by teaching essential life skills such as emotional literacy, problem-solving, conflict resolution and stress management. These programs help youth build internal resources that protect against negative influences and prepare them to navigate life challenges with confidence and calm.

Mental health-focused prevention is not about labeling young people as “at risk” or “dangerous”, it is about seeing their pain, responding with compassion and giving them the tools and support they need to build a better future. When trauma is addressed early, when youth are welcomed into inclusive spaces and when communities are equipped to respond, the pathway to radicalization or criminality can be interrupted before it begins.

Civic Engagement as Prevention of criminality and radicalization

- Volunteering: Getting involved in local projects, environmental clean-ups, or charity events.

- Community Dialogue: Joining youth groups, attending public meetings, organizing round tables or participating in cultural exchanges.

- Advocacy and Storytelling: Sharing personal stories, raising awareness about refugee experiences, or supporting causes through social media and community campaigns.

- Informal Leadership: Taking initiative in peer groups, organizing interactive workshops, helping organize activities, or supporting others in similar situations.

Mentorship, Peer Support, and Exit Programs

Youth need trusted relationships in order to heal, grow, and build a sense of belonging. One of the most effective protective factors against vulnerability—whether to crime, radicalization, or despair—is having someone to talk to who understands their experiences and can guide them forward.

Mentorship and peer-led support models play a critical role in prevention and empowerment. In these models, older youth or adults who have successfully navigated the challenges of displacement, integration, or exiting criminal or extremist environments mentor younger peers. These relationships can take many forms, from informal guidance to structured, long-term programs.

Key Characteristics of Mentorship and Peer Support

- Trusted Relationships: Mentors serve as consistent, reliable figures in a young person’s life—someone who listens without judgment, models positive behaviors, and offers practical advice.

- Role Models: For refugee youth, seeing someone who has faced similar obstacles and built a stable life provides hope and motivation. Mentors demonstrate that positive pathways are possible.

- Safe Spaces for Dialogue: Mentorship programs create environments where young people feel safe to share difficult experiences, ask questions, and express doubts.

- Bridges Between Communities: Mentors may be local youth trained in intercultural understanding, anti-racism, and conflict resolution, helping to build connections between refugee communities and the wider society.

- Life Skills and Goal-Setting: Beyond emotional support, mentors can help youth develop concrete skills—like navigating school systems, finding work, understanding laws, managing finances, or handling conflicts without violence.

- Identity and Belonging: These connections counteract feelings of isolation and alienation by reinforcing a sense of identity and purpose anchored in positive community ties.

🔹 Exit Programs for Criminal and Extremist Involvement

For young people already entangled in gangs or extremist networks, exit programs provide an organized pathway out. These initiatives often work hand-in-hand with mentorship and peer support models to rebuild trust, safety, and self-worth.

Exit programs typically include:

- Individual Counseling: Tailored support to address trauma, identity struggles, and motivations for involvement.

- Practical Assistance: Help with housing, education, vocational training, and legal issues that can keep youth stuck in criminal environments.

- Mentorship from Credible Messengers: Former gang members or individuals who have left extremist groups often act as mentors, using their lived experience to inspire change.

- Safety Planning: Relocation,strategies to protect individuals from retaliation or re-recruitment.

- Family Support: Involving parents or caregivers to strengthen protective networks.

- Community Reintegration: Positive social activities and opportunities to participate in civic life.

These programs recognize that simply punishing or stigmatizing youth rarely works. Instead, they focus on building capacities, addressing underlying needs, and offering real alternatives to crime and extremism.

🔹 Broader Impact of Mentorship and Peer Support

When designed thoughtfully, mentorship and peer support:

- Improve self-esteem and self-efficacy.

- Reduce the likelihood of recruitment into criminal or extremist circles.

- Strengthen resilience against manipulation and exploitation.

- Create ambassadors for positive change, as young people who are mentored often become mentors themselves.

Reducing recruitment through Cross and multi Sectoral Cooperation

To effectively prevent the recruitment of unaccompanied refugee minors and asylum seekers into criminal environments and extremist groups, it is essential to address both individual vulnerabilities and structural conditions that increase risk. This requires cross-sectoral cooperation—a coordinated approach involving schools, child welfare services, police, immigration authorities, civil society organizations, faith communities, and mental health professionals. The list of actors involved is not limited and depends on the individual case and situation!

Key Focus: Remove or Reduce Root Causes of Criminality and Radicalization

To “reduce recruitment to criminal and extremist environments and activities by removing or reducing societal and individual causes and processes,” cooperation must tackle the intersecting risk factors that push refugee youth toward gangs, trafficking networks, or radical groups offering a sense of identity, revenge, or belonging.

Level | Causes/Risk Factors | Cross-Sector Strategies |

|---|---|---|

1. Societal Causes (Structural Level) | – Systemic discrimination and racism in education, housing, and public spaces → exclusion & resentment – Limited access to legal income (work restrictions, poverty) – Long & uncertain asylum processes → hopelessness & distrust – Underfunded integration/inclusion programs → invisibility & rejection – Polarization & stigmatization exploited by extremist recruiters | – Inclusive education & vocational training linked to jobs – Collaboration (municipalities, NGOs, employers) → internships & dignified work – Reduce asylum waiting times & strengthen legal safeguards – Dialogue & trust-building programs to counter exclusion narratives |

2. Individual Causes (Personal Level) | – Trauma & mental health challenges (war, displacement, loss) – Identity crises & alienation → susceptibility to extremist ideologies – Lack of adult guidance or positive role models – Peer pressure & online manipulation (gangfluencing, radical content) – Unaddressed grievances (humiliation, injustice) | – Trauma-informed & culturally sensitive mental health care – Identity-building through sports, arts, & community activities – Youth mentorship by credible messengers (incl. refugees) – Family support & parenting guidance (esp. reunification) – Digital literacy & resilience training against online grooming |

3. Radicalization-Specific Dynamics | – Search for meaning, justice, or revenge after trauma/exclusion – Online echo chambers & extremist recruitment exploiting grievances – Promises of status, respect, empowerment (gangs, extremist groups) – Financial incentives or protection in poverty/insecurity | – Community policing built on trust, not surveillance – Exit programs & deradicalization support – Partnerships with faith-based & community groups → counter-narratives – Early warning systems in schools & social services |

No single actor can address crime and radicalization alone!

Take a look and analyze the Inter Agency coordination meeting.

Effective prevention requires:

- Joint case conferences between police, schools, child protection, health services, and NGOs. The list of actors involved is not limited and depends on the individual case and situation.

- Interdisciplinary outreach teams targeting areas with high vulnerability.

- Data-sharing protocols (with privacy safeguards) to detect early risk patterns.

- Youth-centered interventions designed together with affected communities to ensure trust and cultural relevance.

- Multi-stakeholder networks linking local, regional, and national actors to share good practices and resources.

By removing structural barriers, supporting individual resilience, and building inclusive communities, cross-sectoral cooperation can significantly reduce the recruitment of refugee youth into criminal and extremist environments. Preventive strategies must not only react to threats but also address the root causes that make crime and radical ideologies appear as rational or attractive paths.

Assignment

Assignment: Please explore the models and consider which elements—or the entire model—could be adapted and implemented in your country.

Across different countries, a number of real-world programs have demonstrated how a combination of different approaches can successfully prevent radicalization and criminal behavior among vulnerable youth. These initiatives combine therapeutic support, community engagement and education to address the underlying psychological and social needs that often make young people susceptible to harmful influences. Below are two powerful examples of how these strategies are applied in practice:

- The Hayat Program in Germany HAYAT – Hedayah Website is one of the most well-established initiatives focused on the prevention of Islamist radicalization. The program works directly with individuals at risk of being drawn into extremist ideologies, as well as with their families. A key component of Hayat’s approach is psychosocial counselling, which helps young people process emotional pain, build self-awareness and learn nonviolent ways to deal with anger, identity issues or injustice. The program also offers family therapy, recognizing that a stable, supportive home environment is critical in preventing isolation and reinforcing healthy development. Hayat does not simply aim to “deradicalize” individuals, it focuses on mental health recovery, social reintegration and restoring trust within families and communities.

- The Aarhus Model in Denmark Panorama pdf, Danish preventive measures and deradicalization strategies: The Aarhus model – Aarhus Universityis another pioneering example. It brings together a multi-disciplinary team that includes police, teachers, psychologists, social workers and community mentors. Instead of relying on punishment or surveillance, this model prioritizes care and inclusion. Young people identified as being at risk of radicalization or criminal activity are given access to individual therapy, mentoring and support in returning to education, employment or vocational training. What makes the Aarhus Model particularly effective is its focus on building long-term relationships with the youth, helping them feel seen, heard and valued, key protective factors in mental health. This relationship-based method increases resilience, restores purpose and reduces feelings of exclusion that extremist recruiters often exploit.

Case study #1

🎯 Case 1: Ali

Ali, Age 15

Ali arrived in Europe alone after fleeing armed conflict in Afghanistan. His family had borrowed money to pay a smuggler who promised safe passage and a place to live. During the journey, Ali was held in an overcrowded warehouse where he was threatened with violence if he tried to leave.

When he arrived in the destination country, he was taken by the smuggler to work in an illegal cannabis farm to “repay his debt.” He was told that if he refused, the smuggler would inform the authorities that he had entered illegally, or worse, harm his younger siblings still in Afghanistan.

When a youth worker met Ali through outreach at a local drop-in center, he seemed anxious and avoided eye contact. He spoke of “helping someone” but was vague about the details. Careful, nonjudgmental questioning and trust-building revealed signs of ………..

Questions and correct answer:

Signs of……… (trafficking and criminal exploitation)

Please identify indicators of trafficking and criminal exploitation?

- Debt bondage (“You must work to pay your family’s debt”).

- Threats and intimidation.

- No freedom to leave the work site.

- No payment or documentation.

Case study #2

🎯 Case 2: Sara

Sara, Age 17

Sara fled Syria as a child and spent several years moving between refugee camps. Now in a European city, she struggles with depression and frequent nightmares. She feels alienated at school, where classmates mock her accent and avoid her.

Online, she started connecting with a group that shared videos framing Western society as oppressive and humiliating. A charismatic older female “mentor” began messaging her privately, offering friendship and reassurance that she was part of a greater cause. Over time, Sara was encouraged to adopt extremist beliefs and share content justifying violence as a way to reclaim dignity. Sara’s teachers noticed she had withdrawn completely from class activities and was expressing admiration for extremist figures. Through a school social worker, Sara accessed early mental health support, community mentorship, and culturally adapted counseling to process her grief, rebuild her identity, and find a sense of purpose in safer ways.

Questions and correct answer:

Please identify the process? Radicalization

Please identify indicators of radicalization?

Correct answer:

- Loss of identity and belonging.

- Exposure to radical narratives online.

- Grooming and emotional manipulation by a recruiter.

- Justification of violence as revenge.

Summary

This module has explored the complex, intertwined challenges of human trafficking, radicalization, and criminality among unaccompanied refugee minors and asylum-seeking youth. We have seen that these are not isolated issues, but mutually reinforcing risks driven by:

- Trauma and mental health challenges

- Loss of identity and belonging

- Social exclusion and discrimination

- Manipulation by organized criminal groups and extremist networks

Risk Factor | Impact | Protective Response |

|---|---|---|

Trauma from war/displacement | Emotional distress, distrust, aggression | Early trauma-informed mental health care |

Social withdrawal | Reduced support networks | Outreach, safe spaces, peer engagement |

Isolation & exclusion | Hopelessness, alienation | Community integration activities |

Identity confusion | Loss of belonging | Cultural adaptation, mentorship |

Targeting by recruiters | Manipulation & exploitation | Digital literacy, critical thinking training |

Prevention and intervention require:

✅ Early identification of warning signs

✅ Trauma-informed and culturally sensitive support

✅ Safe spaces and positive relationships that build trust and resilience

✅ Cross-sector cooperation among schools, social services, law enforcement, and communities

✅ Empowerment of youth through civic engagement, education, and mentorship

When professionals understand the root causes and dynamics behind exploitation and radicalization, they can respond with compassion, skill, and effective strategies that protect and empower young people.

The examples shared—from the Hayat Program in Germany to the Aarhus Model in Denmark—show that change is possible when we invest in prevention, build inclusive communities, and prioritize mental health and belonging.

Key Takeaway:

Protecting refugee youth is not only about preventing harm—it is about creating environments where all young people can heal, grow, and contribute positively to society.

By applying the tools, knowledge, and approaches from this module, you are taking an important step toward breaking cycles of exploitation and building safer, more hopeful futures.

References & Further Reading

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Mental Health and Psychosocial Support for Persons of Concern (https://www.unhcr.org/protection/health) – Offers guidance on trauma, displacement-related stress and community-based mental health care.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Preventing Extremism Through Public Health Strategies (2020). (https://www.who.int/publications) – Explores the mental health dimensions of violence prevention and radicalization.

- Council of Europe (2021). Protecting Refugee Children from Radicalisation. (https://rm.coe.int/protecting-children-against-radicalisation) – Reviews risks and protective factors among refugee and migrant youth in Europe.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). Psychosocial Support for Youth in Crisis Contexts. (https://www.iom.int) – Discusses the psychosocial needs of displaced youth and links to prevention work.

- RAN (Radicalisation Awareness Network) Centre of Excellence. Dealing with Trauma and Preventing Radicalisation (2019). (https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network_en) – Details trauma-informed prevention strategies in schools, prisons and community settings.

- The Aarhus Model (Denmark). Bertelsen, P. (2015). Danish Preventive Measures and De-radicalization Strategies. In Journal for Deradicalization, Issue 3.

- Hayat Program (Germany). Koehler, D. (2017). Understanding Deradicalization: Methods, Tools and Programs in Germany. In Journal for Deradicalization, Issue 1.

- STRIVE Program (Canada). John Howard Society of Canada (2021). STRIVE: Supporting Youth to Exit Criminal and Extremist Networks. (https://johnhoward.on.ca/)

- European Commission – Erasmus+ Projects Database. Safety and Success – Prevention of Radicalisation. (https://erasmus-plus.ec.europa.eu/) – Training modules and project outcomes related to adult and youth education in radicalization prevention.

- AEDBG – Association for Education and Development. Prevention of Radicalization Training Outcomes (Corfu, Greece – 2021). (https://aedbg.com/) – Participant learning reflections and prevention strategies related to mental health and community action.

- Silke, A. (2018). Radicalisation, Terrorism and Mental Health: Setting the Agenda. In Nature Human Behaviour, Vol. 2, 19-20. – Examines how mental health intersects with violent extremism risk and prevention.

- Miller, A. B., et al. (2020). Community Interventions to Prevent Youth Violence and Radicalisation. In Psychological Services, 17(1), 67-78.

- Forebygging av ekstremisme og radikalisering | Et nettsted fra RVTS

- Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime | OHCHR

- United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime

- Tore Bjørgo «Forebygging av kriminalitet» Forebygging av kriminalitet – forebygging.no