8. Education/Support in the labour market

Introduction

Description:

This module, Education and Labour Market Navigation for Young Migrants and Refugees, empowers professionals working with unaccompanied minors by combining two key areas: education as the gateway to integration and labour market guidance as the pathway to independence. It highlights the legal right to education, barriers to access, and best practices for ensuring inclusion, resilience, and skills development. Alongside this, it equips professionals to guide young people into the labour market, addressing challenges such as language acquisition, recognition of prior learning, discrimination, and complex legal frameworks. Covering both national education systems and labour market contexts across Belgium, Germany, Spain, Greece, Bulgaria, and Norway, the module provides practical strategies—ranging from school enrolment and vocational pathways to CV writing and career counselling—to ensure smoother transitions into education, training, and meaningful employment

Aim:

To equip professionals with the knowledge and tools to support unaccompanied refugee minors in accessing education and transitioning successfully into the labour market, thereby promoting protection, integration, and independence.

Learning outcomes:

By the end of this module, participants will be able to:

- Understand education as a right and foundation for integration – Recognise international, European, and national frameworks ensuring access to education for refugee minors, and identify barriers (e.g., language, trauma, documentation).

- Apply inclusive educational strategies – Support school enrolment, language acquisition, psychosocial well-being, and access to vocational pathways, including bridging and accelerated learning programmes.

- Map opportunities in partner countries – Analyse the main industries, labour market opportunities, and skill shortages in partner countries (Belgium, Germany, Spain, Greece, Bulgaria, and Norway), and adapt this knowledge to the specific context of the country of residence or interest.

- Navigate labour law frameworks – Understand European and national labour law provisions relevant to young refugees and migrants, with a focus on preventing child labour and economic exploitation.

- Strengthen employability support – Apply effective CV and application-writing strategies, recognise and validate both formal and informal skills, and introduce AI tools to enhance job readiness.

- Advocate holistically – Integrate education and labour market support into a continuum that promotes empowerment, protection, and sustainable independence

Education Pathways for unaccompanied refugee minors

Legal Overview: The Right to Education for Unaccompanied Refugee Minors:

Education for unaccompanied refugee minors is not optional but a binding legal obligation under international and regional frameworks. The 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) recognises education as a fundamental right for every child, regardless of legal or migration status, obliging states to provide free and compulsory primary education and to make secondary education accessible to all. The 1951 Refugee Convention further safeguards refugees’ access to public education on par with nationals. Within Europe, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union affirms the right to education (Article 14) and explicitly prohibits child labour (Article 32), while national legislations in EU and associated states have transposed these rights into domestic law. For professionals, this means that ensuring access to education for unaccompanied refugee minors is both a protective measure and a legal duty. It prevents exploitation, supports integration, and aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 4, which calls for inclusive and equitable quality education for all children, including those displaced by conflict and persecution. However, implementation challenges remain, requiring professionals to navigate complex legal systems and advocate for URMs’ right to education. Education is more than academic instruction; it is a cornerstone of protection, resilience, and empowerment for unaccompanied refugee minors (URMs). It provides a pathway out of vulnerability, preventing exposure to child labour, exploitation, and early marriage. For URMs, education builds the foundation for accessing the labour market by fostering literacy, numeracy, critical thinking, and vocational skills.

Global and Regional Data on Refugee Education

The UNHCR Refugee Education Report 2025 indicates that 46% of school-aged refugee children are out of school, with only 37% enrolled at the secondary level and 9% at the tertiary level. While progress has been recorded in primary enrolment, regional disparities remain stark. For instance, Colombia achieved a near-universal enrollment of Venezuelan refugee children by 2024, while Sudan saw primary enrolment rates collapse due to renewed conflict. In the MENA region, Türkiye expanded secondary enrolment from 27% to 73% between 2019 and 2024, demonstrating how inclusive policies can yield significant results. These statistics reveal the fragility of educational access for refugees and underscore the importance of sustained, targeted investment to close the gaps.

Barriers Faced by Unaccompanied Refugee Minors

Despite the universal recognition of education as a right, URMs face disproportionate barriers. Language acquisition remains one of the greatest challenges, slowing integration into formal education systems. Trauma from displacement, family separation, and conflict undermines concentration and learning. Administrative barriers such as missing documentation, unrecognized prior learning, and unfamiliar curricula further delay school enrolment. Additionally, many URMs experience economic pressures that force them to prioritize survival over schooling, placing them at heightened risk of exploitation and exclusion from both education and future employment.

Providing education for refugee students is often more costly than for host populations, as it requires additional investments in language instruction, psychosocial support, remedial learning, and sometimes infrastructure expansion to accommodate new arrivals (World Bank & UNHCR, 2021). Beyond financial pressures, teachers frequently report that they do not feel adequately prepared to teach in multicultural and multilingual classrooms. Many lack training in inclusive pedagogies, trauma-informed approaches, and strategies for integrating students with diverse educational backgrounds. Without sufficient support, both in professional development and classroom resources, teachers may struggle to deliver quality instruction that meets the needs of all learners. Addressing these gaps is critical—not only to ensure equity in learning outcomes for refugee minors but also to strengthen the overall capacity of education systems to respond effectively to diversity.

Education system

Education is one of the most powerful tools for the integration and empowerment of unaccompanied refugee minors (URMs). It provides not only academic skills but also a pathway to social inclusion, language acquisition, and emotional stability. Yet, many URMs face barriers such as interrupted schooling, language gaps, unfamiliar curricula, and limited understanding of their rights to education. Establishing a clear, accessible, and supportive education pathway is essential for their successful integration.

Key Components of Education System Integration for Unaccompanied Refugee Minors (URMs)

📂 Area | 💡 Main Focus | 🧩 Key Actions / Strategies | 🎯 Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

School Orientation & Enrollment | Early access to education and understanding the system | – Develop a multilingual School Welcome Pack

– Explain enrollment process & required documents – Provide overview of school expectations & supports – Clarify roles of teachers, counselors, interpreters | ✅ Early school enrollment

✅ Stability and structure ✅ Better community participation |

Language Support | Building communication and learning capacity | – Offer intensive or “welcome” language classes

– Create peer-assisted learning programs – Provide multilingual learning materials & apps – Partner with NGOs for after-school language clubs | ✅ Improved language skills

✅ Social inclusion ✅ Greater classroom participation |

Academic & Career Guidance | Bridging educational gaps and future planning | – Assess academic level, not only age

– Provide bridging or remedial programs – Offer career guidance on vocational & higher education – Share info on scholarships & free training | ✅ Equal access to education

✅ Clear career pathways ✅ Empowered and goal-oriented youth |

Psychosocial & Trauma-Sensitive Support | Addressing emotional well-being and resilience | – Train teachers in trauma-informed practices

– Provide access to counselors and safe spaces – Encourage open communication & trust | ✅ Emotional stability

✅ Reduced dropout rates ✅ Supportive and safe school environment |

Parental / Guardian Engagement | Inclusion of guardians and mentors in education | – Give regular updates on progress

– Invite guardians to meetings with interpreters – Offer workshops to support learning at home | ✅ Strengthened support network

✅ Better academic outcomes ✅ Improved guardian-student connection |

NGO & Community Partnerships | Supplementing formal education | – Provide tutoring and study groups

– Connect to online learning platforms – Offer free educational resources | ✅ Equal learning opportunities

✅ Reduced educational gaps ✅ Stronger community integration |

Pathways to Further Education & Employment | Transitioning to adulthood and independence | – Offer vocational training & apprenticeships

– Provide job readiness workshops – Give info on work permits & visas – Align education with employment plans (including health aspects) | ✅ Smooth transition to adulthood

✅ Employment readiness ✅ Economic independence |

NGOs and schools can work together to create transition-to-adulthood plans that align education and employment. And of course, do not forget to include health aspects in this plan!

By ensuring early enrollment, language support, tailored academic guidance, and trauma-sensitive teaching, URMs can build the skills, confidence, and qualifications they need to succeed in the host country. Education becomes not only a right but a foundation for lifelong integration, economic independence, and active citizenship.

Case studies & best practices

Best Practices in Refugee Education for URMs

Best practices highlight the importance of inclusive national policies that guarantee access to public education systems. Homework support initiatives—such as the involvement of retired teachers—are vital for bridging academic gaps while fostering trust and cultural orientation. Psychosocial support and trauma-informed teaching approaches ensure that learning environments are sensitive to the lived experiences of URMs. Bridging and accelerated learning programmes allow URMs to catch up academically and transition smoothly into mainstream schools. Language support, particularly intensive host-country language courses, is indispensable for ensuring long-term success.

Case Studies 1

In Colombia, policy reforms supported by the Quito Process led to an enrolment increase from 48% to 99% for Venezuelan refugee children between 2019 and 2024. Türkiye’s large-scale inclusion of Syrian children into national schools enabled secondary enrolment to grow significantly within five years. In Jordan, public schools absorbed refugee students with support from international partners, though resource limitations constrained progress. These examples illustrate how policy, partnerships, and investment can dramatically alter education outcomes, providing valuable lessons for European contexts.

Case study 2

Case Scenario

Homework Help as a Pathway to Trust, Integration, and Well-Being

Safe Spaces is launching a new initiative to support unaccompanied refugee minors. The program seeks to recruit retired teachers as volunteers to provide homework help. Beyond academic support, the goal is to build trust, reduce isolation, and help minors adjust to the culture and norms of their new community.

The minors often face:

- Academic challenges due to language barriers and gaps in formal schooling.

- Social isolation from peers and limited connection to supportive adults.

- Stress, anxiety, and uncertainty about the future.

The retired teachers, in turn, benefit from meaningful engagement, a sense of purpose, and opportunities to positively impact young lives.

Assignment Tasks

- Identify Benefits for Both Groups

- List at least three benefits for the minors.

- List at least three benefits for retired teachers.

Challenges & Risks

- What potential challenges might arise for minors receiving this help?

- What challenges might volunteer face (e.g., cultural differences, emotional strain)?

- Propose at least two strategies to mitigate these risks.

Program Design

- Suggest a structure for how homework help sessions could be organized (frequency, setting, matching process).

- Propose one way to integrate cultural exchange (e.g., sharing traditions, language practice).

Recruitment Strategy for Retired Teachers

- Outline at least three methods for recruiting retired teachers (e.g., partnerships, community outreach, incentives).

- Suggest ways to motivate and retain them (e.g., recognition, social gatherings, ongoing training).

- Identify potential barriers to recruitment and how to overcome them.

Impact on Well-being

- Explain how homework support can improve:

- Academic success

- Mental health

- Social integration

- Give one example of how this support could lead to long-term benefits for a minor.

Reflection

- Imagine you are a retired teacher volunteering in this program. Write a short reflection (5–7 sentences) on why this work would be meaningful for you.

Digital and Innovative Education Opportunities

The rise of digital and blended learning has opened new avenues for URMs to access education. Online platforms offer flexible and scalable solutions to overcome barriers of mobility, capacity, and access. Examples include regional digital higher education initiatives and mobile-based language learning apps. Technology companies, NGOs, and host governments have begun to collaborate on expanding connectivity, device provision, and digital literacy training. Such innovations complement traditional schooling and vocational training, helping URMs acquire essential digital skills increasingly demanded in modern labour markets.

Integrating academic subjects with sports and physical activity is highly effective, especially in settings with refugee or displaced youth, where engagement, trauma-informed practices, and holistic learning are crucial. This interdisciplinary approach supports physical, cognitive, and emotional development simultaneously.

Below is a sample curriculum framework followed by concrete examples per subject.

- Integrated Curriculum: Academics Through Sports & Physical Activity Goals:

- Reinforce academic concepts through kinesthetic learning

- Promote teamwork, confidence, and communication

- Address trauma and displacement through structured, meaningful play

- Make learning accessible, engaging, and relevant to real life

- Curriculum Structure (Weekly Model)

Day | Focus | Integrated Subjects | Sports Activity | Learning Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Mon | Numbers in Action | Math + PE | Team relay with score tracking | Practice addition, subtraction, percentages |

Tue | Body & Movement | Science + Health | Obstacle course | Learn human anatomy, joints, energy use |

Wed | Word Games | Language + Drama | Sports storytelling | Build vocabulary, communication skills |

Thu | Cultural Team Games | Social Studies + Ethics | Traditional games from various cultures | Learn about diversity, empathy |

Fri | Art in Motion | Arts + Geometry | Dance or rhythm-based games | Explore shape, rhythm, creative expression |

- Examples by Subject

🧮 Math

- Relay Race Scorekeeping: Students track lap times, calculate averages, compare fractions.

- Basketball Angles: Learn about angles and trajectory through basketball shots.

- Volume & Distance: Estimate and measure how far a ball travels; convert units (meters to feet).

🔬 Science

- Body Systems & Exercise: Label body parts, muscles used in a specific movement (e.g., lunges).

- Heart Rate Experiment: Compare resting vs. active heart rates; graph results.

- Physics of Sport: Explore force, friction, balance, and gravity using balance beams or balls.

🗣️ Language & Literacy

- Sports Journalism: Write or present a match recap or interview a teammate.

- Movement & Vocabulary: Use charades or physical storytelling to learn new words.

- Team Chant Writing: Compose original chants or poems about fair play and teamwork.

🎨 Arts

- Choreograph a Story: Use movement to represent a historical event or folk tale.

- Sports Equipment Design: Create logos, uniforms, or custom game tools with local materials.

- Shadow Play: Use body movement and props to act out scenes or feelings.

🌐 Social Studies & Citizenship

- Cultural Games Week: Introduce sports from different refugee communities (e.g., kabaddi, sepak takraw).

- Ethics in Sport: Discuss fairness, inclusion, and leadership roles.

- Mapping Movement: Use maps to chart Olympic locations or origins of traditional games.

🎯 Why It Works

- Culturally adaptable: You can adjust games and academic levels to suit the background of participants.

- Low-resource friendly: Many activities can be done with found objects, hand-drawn charts, or natural space.

- Inclusive & trauma-informed: Movement supports healing, while integrated learning keeps students engaged.

- Multilingual & multi-level adaptable: Activities can be taught through visuals, movement, and peer support.

The Role of Education in Labour Market Integration

In the context of labour market integration, education serves as the essential bridge between dependency and independence, enabling refugee youth to acquire both the competencies and confidence required to thrive in their host societies. For unaccompanied refugee minors, education is not only about classroom learning—it is the entry point to social inclusion, personal development, and long-term stability. By attending school, they gain critical literacy and numeracy skills, but just as importantly, they develop resilience, problem-solving abilities, and social competencies that employers increasingly value.

Education also functions as a protective factor. Refugee youth who remain in school are less vulnerable to child labour, economic exploitation, or recruitment into illicit activities. Schools provide a structured environment that fosters safety, belonging, and peer support, all of which contribute to improved mental health and readiness for the workplace. Moreover, exposure to the host country’s language, culture, and civic values in educational settings builds intercultural competence—an essential attribute in today’s diverse labour markets.

Equally important, education helps prevent social exclusion and the identity crises that many unaccompanied minors face when adapting to a new society. Displacement often disrupts a young person’s sense of self and belonging, leaving them caught between their cultural heritage and the demands of a host community. Schools offer a space where identities can be nurtured positively: by learning alongside peers, participating in extracurricular activities, and experiencing recognition of their backgrounds, refugee minors can build a stronger and more stable self-concept. This process reduces feelings of marginalisation and helps them avoid the isolation that may otherwise hinder integration and employment prospects.

From an economic perspective, education directly impacts employability. Research consistently shows that higher levels of schooling translate into better job prospects, higher wages, and increased economic participation. For refugee minors, even partial secondary or vocational education can make the difference between long-term unemployment and meaningful, dignified work. Technical and vocational education and training (TVET), apprenticeships, and digital learning platforms provide practical pathways into industries experiencing labour shortages, such as healthcare, skilled trades, and information technology.

Finally, education plays a systemic role in integration. Host societies benefit when refugee youth are empowered to contribute productively rather than becoming excluded or marginalised. Schools and vocational institutions act as bridges between young refugees and local employers, creating opportunities for mentorship, internships, and job placements. In this way, education serves not just the individual, but also strengthens communities and labour markets by cultivating a workforce that is skilled, adaptable, and diverse.

Vocational Education and Training (VET)

Vocational pathways are essential in linking education to the labour market, especially for young people who may not pursue traditional academic routes. Germany’s Dual System, which combines classroom learning with apprenticeships, exemplifies how refugees can gain practical experience while continuing their studies. This model has proven particularly effective in helping young migrants acquire not only technical skills but also workplace habits, social networks, and an understanding of the host country’s professional culture.

Other European countries are also expanding vocational training initiatives, especially in sectors where labour shortages are acute, such as healthcare, construction, skilled trades, hospitality, and digital professions. These programs often include language support, mentoring, and cultural orientation, making them accessible for unaccompanied refugee minors (URMs) who may struggle with mainstream schooling. In some contexts, accelerated vocational tracks allow URMs to catch up on missed years of education while gaining qualifications recognised across the EU, thus improving mobility and long-term prospects.

Drawing on the Cedefop VET Systems in Europe project, it becomes clear that European countries display a rich diversity in how they organise VET—but with common success factors that are especially relevant for unaccompanied refugee minors (URMs). Key among these are strong public-private cooperation (especially in apprenticeship schemes), financing models that cover not just institutional costs but also learner support (travel, tools, living expenses), and robust guidance and validation mechanisms to accommodate prior learning in non-formal or informal settings:

Financing arrangements CEDEFOP+2 that share costs among multiple stakeholders: governments, employers, sometimes learners themselves. States often offer subsidies, stipends, or accommodation support to apprentices (or students in VET) to reduce barriers of cost.

Validation of non-formal and informal learning (NFIL or RPL – recognition of prior learning)CEDEFOP+2CEDEFOP+2 so that young people whose studies have been interrupted — or who have gained skills outside formal schooling — can have those skills recognised. This helps URMs enter VET at appropriate levels without unnecessary repetition.

Apprenticeships and work-based learningCEDEFOP+2CEDEFOP+2, which Cedefop highlights as helping smoother school-to-work transitions. Apprenticeships make VET more directly connected to labour market needs, and provide URMs with both skills and a path into employment.

Policy flexibility and subsidies for learnersCEDEFOP+2CEDEFOP+2, such as financial incentives, grants, or allowances to cover extra costs (transportation, tools, living expenses), so that URMs, who may have limited financial support, are not excluded from VET opportunities.

System adaptabilityCEDEFOP+1: VET providers in some countries are able to adjust their offerings according to labour market demands (green economy, digital skills, healthcare etc.), which is crucial for ensuring that training for URMs leads to employment.

For URMs, these features are vital: they ensure that vocational training is affordable, relevant, and navigable. Moreover, elements such as mentorship, career counseling, and recognition of past skills help bridge gaps caused by interrupted education, making VET a viable path toward stable employment and integration.

Case study

Vocational education and training in Europe

VET in Europe database – detailed VET system descriptions

Case:

Please compare German and Norwegian VET systems with the country you represent:

Germany – The Dual System (widely seen as a benchmark in Europe)

- Structure: Combines classroom learning (in vocational schools) with paid apprenticeships in companies.

- Scale: Very large and institutionalised; about half of German youth enter VET pathways.

- Employer involvement: Companies are heavily involved, shaping curricula and financing training, ensuring close alignment with labour market needs

- Strengths:

- Extremely effective for smooth school-to-work transitions.

- Strong reputation among employers → high employability.

- Deep integration with industry sectors (automotive, engineering, healthcare, etc.).

- Challenges:

- Entry requirements can be demanding for refugees/URMs (language proficiency, documentation).

- Less flexibility once enrolled; difficult to change fields mid-training.

Norway – Flexible, socially supportive VET

- Structure: Typically 2 years in school + 2 years apprenticeship (“2+2 model”), though flexible pathways exist.

- Focus: Balances labour market needs with social inclusion and welfare principles.

- Strengths:

- High degree of flexibility → allows tailored pathways for vulnerable groups, including URMs.

- Strong welfare support: apprentices often receive financial allowances and integration support.

- Emphasis on emerging sectors (green energy, aquaculture, healthcare).

- Smaller system than Germany, making it more adaptable and personalised.

- Challenges:

- Fewer apprenticeship placements compared to Germany → not all students find a training company.

- Less international recognition than Germany’s system.

- Smaller scale and less global visibility.

Watch the following videos to get more understanding about VET in European Countries:

https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/videos/vocational-education-and-training-system-romania-snapshot

https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/videos/vocational-education-and-training-vet-finland

https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/videos/vocational-education-and-training-vet-system-croatia

Career counseling and recognition of past skills

Career counseling is essential for unaccompanied refugee minors, helping them understand available educational and vocational options, identify their strengths, and make informed decisions about future pathways. Many URMs arrive with prior skills or informal work experience that often goes unacknowledged. Recognition of past learning—whether through formal procedures like recognition of prior learning (RPL) or through tailored assessments—ensures that these competences are valued and can be built upon. When combined with individualized career guidance, this recognition prevents skill loss, shortens integration time, and increases the likelihood of sustainable employment outcomes.

For more information, please refer to module 4 Career guidance.

Recommendations for Professionals

Professionals working with URMs should prioritise guiding them through education-to-employment transitions. Key recommendations include advocating for early and sustained access to education; providing structured language and academic support; linking young people to vocational pathways aligned with labour shortages; and offering mentoring, career guidance and psychosocial care. Equally important is supporting URMs in recognising and articulating their existing skills—both formal and informal—to increase their employability. Close collaboration with schools, training institutions, employers, and legal guardians is critical to ensure that URMs are supported holistically. Education is not simply preparation for employment, it is a protective, empowering, and transformative force in the lives of unaccompanied refugee minors. It shields them from exploitation, builds resilience, and opens pathways to meaningful work and independence. By embedding education at the heart of labour market integration strategies, professionals, policymakers, and communities can ensure that URMs are not only prepared for jobs but also for active, dignified participation in society. The integration of education and labour market preparation is thus both a moral obligation and a practical necessity for sustainable inclusion.

Introduction to Labour Market

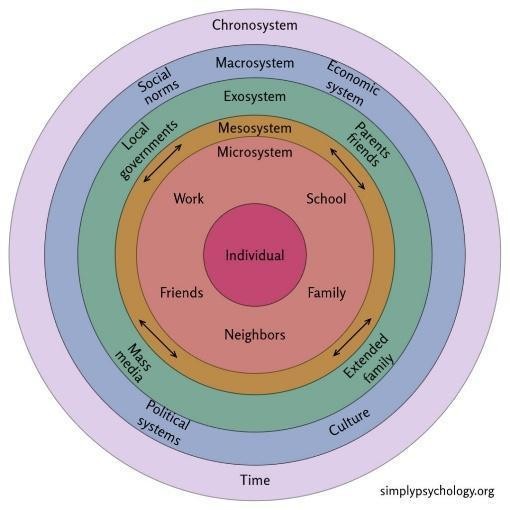

To truly understand the complexities faced by young migrants and refugees in the labour market, this module adopts a holistic approach, specifically drawing upon the Ecological Perspective Theory. Developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner, this theory posits that an individual’s development is influenced by various interconnected environmental systems. For young migrants and refugees, their journey into the labour market is not an isolated event but rather a dynamic interaction within multiple layers of their environment:

- Microsystem: This includes the immediate environments, such as their family (if applicable), peers, and the migrant welcoming centre where you work. Your direct interactions and the support networks you help build are crucial here.

- Mesosystem: This refers to the interactions between different microsystems. For example, the connection between the welcoming centre and local employers, or between the young person’s educational institution and potential workplaces.

- Exosystem: This encompasses external settings that indirectly affect the young person. Examples include local government policies on employment, community attitudes towards migrants, and the availability of public transportation to job sites.

- Macrosystem: This represents the broader cultural values, laws, customs, and socioeconomic conditions. European and national labour laws, prevailing attitudes towards migration, and the economic climate of the host country all fall within this layer.

- Chronosystem: This dimension accounts for the influence of time and historical changes on these systems. The evolving nature of migration policies, economic crises, or technological advancements (like AI in job searching) are examples of chronosystem influences.

Figure 1. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory – developed by SimplyPsychology

By applying this ecological lens, we recognise that a young migrant’s success in the labour market is not solely dependent on their individual skills or efforts. It is deeply intertwined with the support systems available, the legal and policy frameworks in place, the broader societal context, and how these various layers interact.

Mapping industry and labour market opportunities

Understanding the specific labour market dynamics of each partner country is crucial for providing targeted and effective guidance. While economic landscapes are fluid, certain industries consistently present opportunities or face significant labour shortages.

- Case Assignment: Mapping Labour Market Dynamics in Your Country

To apply the provided strategy to analyze the labour market dynamics of your country, identify key opportunities and challenges, and recommend targeted guidance for the workforce.

Exploration of Main Industries and Economic Strengths

This sub-section will provide an overview of the main industries and economic strengths of partner countries (Belgium, Germany, Spain, Greece, Bulgaria, and Norway), which ought to be always contrasted by up-to-date local information as the European and national labour market changes and technological advances make the situation evolve.

Belgium:

- Main Industries: Services (especially finance, healthcare, and education), manufacturing (automotive, chemicals, food and beverages). Manufacturing remains significant, notably in automotive, chemicals, and food and beverages. Its central European location makes logistics and transport, especially through major ports like Antwerp, a key economic pillar. Biotechnology is also a growing area (CEDEFOP, n.d.a; Economy of Belgium, n.d.).

- Economic Strengths: Belgium benefits from a highly developed infrastructure, a strong export orientation, a skilled and multilingual workforce, and its strategic position as a hub in Europe. Services account for a substantial portion of its GDP (European Commission, 2024b).

Figure 2. Belgian flag. source: Pexels. Author: pauldeetman

Germany:

- Main Industries: Germany is renowned for its manufacturing sector, particularly in automotive, mechanical engineering, chemicals, and electrical engineering. The service sector, including IT and healthcare, accounts for the largest share of GDP, reflecting a diversified and advanced economy (GTAI, n.d.; European Commission, 2024c).

- Economic Strengths: Germany is the largest economy in Europe, characterised by strong innovation capacity, a highly skilled workforce, and its status as a leading global exporter. Its well-established vocational training system (Dual System) is a significant contributor to its skilled labour force (GTAI, n.d.)

Figure 3. German flag. Source: Pexels. Author: ingo

Spain:

- Main Industries: Tourism is a cornerstone of the Spanish economy, alongside a significant agricultural and food processing sector. Other important industries include the automotive sector, renewable energy, and a growing technology sector, particularly in major urban centres like Madrid and Barcelona (European Commission, 2024e).

- Economic Strengths: Spain possesses a diversified economy, a strong appeal as a global tourism destination, and increasing investments in green technologies. Its strategic geographical position connects Europe with Africa and Latin America, facilitating trade and cultural exchange.

Figure 4. Spanish flag. Source: Pexels Author: Pixabay

Greece:

- Main Industries: Tourism and shipping are the dominant pillars of the Greek economy. Other notable sectors include agriculture, food processing, and pharmaceuticals. While still developing, the technology sector is emerging, and ongoing infrastructure projects are creating new economic opportunities (Enterprise Greece, n.d.; European Commission, 2023a).

- Economic Strengths: Greece benefits from its immense tourism potential, a strategic maritime location, and a growing focus on digital transformation initiatives aimed at modernising its economy (Enterprise Greece, n.d.).

Figure 5. Greek flag. Source: Pexels. Autho: andersbk

Bulgaria:

- Main Industries: Information technology, particularly IT outsourcing, is a significant and rapidly growing area. Other important sectors include automotive components, light manufacturing, agriculture, and tourism (Coface, n.d.; EURES, n.d.b).

- Economic Strengths: Bulgaria offers competitive labour costs, a skilled workforce in IT, and a strategic location within Southeast Europe. Its full membership in the EU further strengthens its economic ties and access to the single market (Coface, n.d.).

Figure 6. Bulgarian flag. Source: Pixabay. Author: jorono

Norway:

- Main Industries: The petroleum sector (oil and gas) is a cornerstone of the Norwegian economy, complemented by a strong seafood industry (aquaculture and fisheries), shipping, and renewable energy (primarily hydropower). The public sector also plays a substantial role (International Trade Administration, n.d.; Statistics Norway, 2023).

- Economic Strengths: Norway’s economy is highly robust, driven by its rich natural resources, high living standards, and a comprehensive welfare system. There is an increasing focus on developing green industries and advanced technologies (International Trade Administration, n.d.).

Figure 7. Norwegian flag. Source: Pixabay. Author: Corentin Julliard

Professional shortage and priority areas

Identification of Professional Shortages and Priority Areas for Labour Force Needs

Understanding skill shortages is vital for guiding young people towards promising career paths and relevant training. These shortages often reflect demographic shifts, technological advancements, and economic priorities.

Common Areas of Shortage Across Multiple Countries (with variations in intensity):

- Healthcare: Across Europe, including in Belgium, Germany, and Greece, there is a consistent and acute demand for healthcare professionals, such as nurses, doctors, and caregivers. This is primarily driven by an aging population and increasing healthcare needs (EURES, n.d.b; European Labour Authority, 2024; Group Working, 2025).

- IT and Digital Professions: The digital transformation is accelerating across all partner countries, creating a high demand for skilled IT professionals. Roles such as software developers, cybersecurity specialists, data analysts, and IT support are universally sought after (EURES, n.d.c; GTAI, n.d.; Cedefop, 2025).

- Skilled Trades: Skilled trades are experiencing widespread shortages as experienced workers retire and fewer young people enter these fields. This includes occupations such as electricians, plumbers, carpenters, welders, and mechanics. This is a significant issue in countries like Belgium and Norway (EURES, n.d.a; EURES, n.d.e; BBVA Research, 2025).

- Hospitality and Tourism: In countries where tourism is a major industry, such as Spain and Greece, there are frequent and significant shortages of workers in roles like cooks, waiters, and hotel staff, particularly during peak seasons (Think Europe, 2025; European Labour Authority, 2024; EURES, n.d.d).

- Engineering: Various engineering disciplines, including civil, mechanical, and electrical, are consistently in demand, especially in Germany‘s strong manufacturing and automotive sectors and in Norway’s energy industry (Group Working, 2025; International Trade Administration, n.d.).

- Logistics and Transportation: Shortages of truck drivers, warehouse workers, and logistics coordinators are a recognised issue in the EU. This is a key concern in countries with strong export-oriented economies (EURES, n.d.a; European Labour Authority, 2024).

Strategies for Professionals:

- Stay Informed: Regularly consult national and regional labour market reports, public employment service data (like Spain’s Observatorio de las Ocupaciones), and publications from organisations like EURES to stay up-to-date on specific and evolving skill shortages.

- Vocational Training Guidance: Guide young people towards Vocational Education and Training (VET) programs that align with identified skill shortages. Many countries, particularly Germany with its “Dual System,” have robust VET programs that can lead to stable, high-demand employment.

- Language Skills: Emphasise the critical importance of host-country language proficiency, as it is often a primary barrier to accessing skilled employment, even in sectors with high demand (Group Working, 2025).

- Transferable Skills: Help young people identify how their existing skills, even from informal work or experiences in their home countries, can be adapted to meet the demands of shortage occupations.

- Digital Literacy: Promote digital literacy and basic IT skills, as these are increasingly essential across all sectors and often a prerequisite for many of the shortage occupations.

Introduction to European & National Law

Navigating the legal landscape is paramount to ensuring the protection and rights of young migrants and refugees in the labour market. This section provides an overview of critical labour law aspects, with a strong emphasis on preventing child labour and economic exploitation. It is crucial to remember that legal frameworks are complex and subject to change; this information serves as a foundation for further consultation with legal experts where necessary.

Focus on Preventing Child Labour and Economic Exploitation

European Union law provides a foundational layer for labour rights, which is then transposed and elaborated upon by national legislation. For non-EU member Norway, its agreements with the EU often align its labour laws closely with EU directives, ensuring a similar level of protection. The key legal instrument governing this area is Council Directive 94/33/EC on the protection of young people at work (EUR-Lex, n.d.).

Key Principles of European Labour Law relevant to Young Workers:

- Minimum Age for Employment: Generally, the minimum age for employment in the EU is 15 years, or the age at which compulsory schooling ends, whichever is higher. Exceptions are made for “light work” for those aged 13-14, as well as for cultural, artistic, and sports activities, with prior authorisation from a competent authority (European Commission, n.d.c; EUR-Lex, n.d.).

- Working Time: The directive sets strict limits on working hours for young workers. For example, adolescents (those aged 15-18 who are no longer in compulsory schooling) generally have a maximum working week of 40 hours. Children (under 15) are limited to a maximum of 2 hours on a school day and 12 hours per week, with these limits expanding slightly during school holidays (Atena, n.d.). Night work is prohibited for young people, with specific hours defined to protect their rest and education.

- Rest Periods: Young workers are entitled to mandatory rest periods. This includes a minimum daily rest period of at least 12 consecutive hours and a minimum weekly rest period of two consecutive days (EUR-Lex, n.d.). These regulations are in place to prevent overwork and ensure adequate time for recovery and personal development.

- Health and Safety: Employers have a legal obligation to protect young workers from hazards. The directive mandates specific provisions to protect them from work that is beyond their physical or mental capabilities, exposes them to dangerous substances, or has a high risk of accidents. Employers must conduct a risk assessment before a young person begins work and provide necessary training and supervision (EUR-Lex, n.d.).

- Fair Treatment: As outlined by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, all workers, including young migrants and refugees, are protected from discrimination based on nationality, origin, or other protected characteristics. The prohibition of child labour and the protection of young people at work is explicitly stated in Article 32 of this Charter (Synergy, n.d.).

- Wages: While there isn’t a harmonised EU minimum wage, the principle of fair wages is promoted. Most member states have national minimum wage laws, which also apply to young workers, though the specific rates may vary based on age or experience.

This framework is crucial for you, as a professional, to understand. It provides the legal basis for advocating for the rights of the young people you support and ensuring their employment is safe, fair, and does not compromise their education or well-being.

National Specifics for Unaccompanied Young Refugees and Minors (General Principles)

📂 Category | 💡 Main Focus | 🧩 Key Actions / Strategies | 🎯 Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

Legal Status & Labour Market Access | Varies by country depending on asylum status, age, and stay duration | – Confirm national rules with legal experts or employment services

– Labour access typically within 9 months (EU Directive 2013/33/EU) – Priority may be given to EU citizens or long-term residents | ✅ Legal clarity for each case

✅ Fair and compliant employment pathways |

Age of Majority & Employment Rules | Defines when minors can work | – Majority age: 18

– Some allow work from 16–17 with guardian consent – Employment must not interfere with education or well-being | ✅ Safe, age-appropriate work participation

✅ Protection of minor workers’ rights |

Education First Principle | Education as the main integration tool | – Education and vocational training prioritized

– Employment allowed only after significant academic progress – Work seen as complementary to education | ✅ Strong educational foundation

✅ Balanced learning and work opportunities |

Supervision & Legal Guardianship | Guardians ensure legal and safe work engagement | – Guardian/state authority must consent to work

– Must ensure work does not harm education or health – Oversee working conditions and rights compliance | ✅ Protection from exploitation

✅ Guardian involvement in all employment decisions |

Belgium | Highly protective approach | – Work permitted after 4 months for asylum seekers

– Specific permits needed for minors – Education attendance is prioritized | ✅ Controlled access

✅ Emphasis on continued schooling |

Germany | Strong legal framework for youth work | – Governed by Jugendarbeitsschutzgesetz (Youth Employment Protection Act)

– Strict limits on hours and work types – Labour access after 6 months | ✅ Safe working conditions

✅ Legal protection for minors |

Spain | Expanding access through reforms | – Minimum work age 16 with guardian consent

– Asylum seekers can work after 6 months – Reforms allow 16–18-year-olds under care to get work & residence permits | ✅ Increased employability

✅ Simplified permit access for youth in care |

Greece | Fast labour market access with protection | – Labour access after 2 months of asylum application

– Guardians appointed for vulnerable minors – Support for vocational training integration | ✅ Early inclusion in training and work

✅ Strong guardianship protections |

Bulgaria | Early access with child protection oversight | – Labour access after 3 months

– Social worker required in legal proceedings – Emphasis on consultation and safety | ✅ Social support involvement

✅ Compliance with child protection standards |

Norway | Tiered system based on age and residence status | – Minimum work age 15, light work from 13 with supervision

– Non-EU/EEA refugees need residence permits allowing work – Governed by the Working Environment Act | ✅ Regulated youth employment

✅ Work linked to protection status |

This overview provides a solid foundation, but the complexity of these regulations highlights the need for professionals to continuously consult with national legal experts and the relevant public authorities to ensure the guidance provided is accurate and tailored to each young person’s specific circumstances.

Focus on Preventing Child Labour and Economic Exploitation

The vulnerability of unaccompanied young refugees and migrants makes them particularly susceptible to child labour and economic exploitation. Professionals must be vigilant and equipped to identify and address these risks.

What is Child Labour?

The International Labour Organization (ILO) defines child labour as “work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to their physical and/or mental development.” It is work that interferes with their schooling, obliges them to leave school prematurely, or requires them to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work (ILO, n.d.a). The worst forms of child labour, as defined by ILO Convention No. 182, include all forms of slavery, such as the sale and trafficking of children, debt bondage, forced labour, and the use of children for illicit activities (ILO, n.d.b).

Indicators of Potential Exploitation:

Professionals should be aware of the following indicators, which can signal that a young person may be a victim of exploitation or trafficking. These signs are often highlighted in reports from organisations like the European Commission and the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (European Commission, 2025; FRA, n.d.).

- Below Legal Working Age: Any work performed by a child below the legally permitted minimum age for employment, as defined by national law and ILO conventions.

- Excessive Hours: Working hours that are unusually long, prevent school attendance, or extend late into the night, thus interfering with a child’s right to education and rest.

- Hazardous Conditions: Engagement in dangerous or unhealthy work environments, or tasks unsuited for their age. This can include work with dangerous machinery, exposure to hazardous substances, or working in confined spaces.

- Unpaid or Underpaid Work: Receiving no pay, very low wages, or wages significantly below the legal minimum wage.

- Debt Bondage/Forced Labour: Being forced to work to pay off a real or alleged debt, or being unable to leave employment freely due to threats or coercion.

- Isolation and Control: Being isolated from social networks, having identity or travel documents withheld, or facing threats and intimidation from an employer or trafficker.

- Lack of Contracts/Informal Work: Working without a formal contract, social security, or other legal protections, which makes them highly vulnerable.

- Physical or Psychological Harm: Showing signs of fatigue, injury, fear, anxiety, or depression that may be linked to their work conditions.

Figure 8. Young worker. Sources: Pexels. Author: mikhail nilov

Role of Professionals in Prevention

As a professional, your role is paramount in protecting these vulnerable individuals. The European Commission and international bodies emphasise the importance of a multi-faceted approach to child protection in migration settings (European Commission, 2025).

- Education and Awareness: Educate young people about their labour rights, the dangers of exploitation, and where to seek help.

- Vigilance and Observation: Be aware of the signs of exploitation in the young people you support, and maintain an environment of trust where they feel safe to share their concerns.

- Legal Guidance: Ensure young people’s employment aligns with national labour laws, especially regarding age, working hours, and type of work.

- Promote Formal Employment: Encourage and assist in seeking formal, legal employment with contracts and social security.

- Reporting Mechanisms: Know the national and local agencies responsible for investigating child labour, labour exploitation, and human trafficking (e.g., labour inspectorates, police, and social services). The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) highlights the need for safe and effective reporting mechanisms for exploited workers (FRA, n.d.).

- Collaboration: Work with legal aid organisations, NGOs, and child protection services to ensure comprehensive support and intervention.

- Secure Living Conditions: Advocate for stable and safe living conditions for unaccompanied minors, as insecurity can push them into exploitative situations (UNICEF, n.d.).

- Psychosocial Support: Provide or facilitate access to psychosocial support for those who may have experienced exploitation, helping them recover from trauma and rebuild their lives.

Training in CV and Application Writing

Effective CVs and job applications are critical gateways to employment. For young migrants and refugees, crafting these documents can be particularly challenging due to language barriers, unfamiliarity with local norms, and difficulty articulating their experiences. This section will provide practical guidance, including the innovative use of AI tools.

Guidance on Identifying and Articulating Soft Skills and Hard Skills

A strong application highlights both “hard” and “soft” skills. Helping young people identify and articulate these is a crucial step.

- Hard Skills: These are measurable, teachable abilities that are often specific to a job or industry. They can be learned through education, training, or on-the-job experience.

- Examples: Fluency in a specific language (e.g., Arabic (Dariya) or Urdu, alongside host country language), driving license, proficiency in software (e.g., Microsoft Office, design tools), specific vocational skills (e.g., carpentry, welding, cooking, basic coding), data entry, operating machinery.

- How to Identify: Ask about formal training, previous work (even informal), hobbies that involve technical skills, and educational achievements.

- How to Articulate: Use clear, concise language. Quantify achievements where possible (e.g., “Managed a database of 200 clients,” “Operated machinery to produce 50 units per hour”).

- Soft Skills: These are interpersonal, personal, and communication attributes that are less tangible but crucial for success in any workplace. They are often transferable across different jobs and industries.

- Examples: Adaptability, problem-solving, teamwork, communication (verbal and written), resilience, time management, critical thinking, reliability, initiative, empathy, cultural awareness, conflict resolution.

- How to Identify: Encourage reflection on past experiences (school, volunteer work, community involvement, even their migration journey). Ask questions like:

- “Tell me about a time you had to work with others to achieve a goal.” (Teamwork)

- “How did you handle a difficult situation or unexpected challenge?” (Problem-solving, adaptability, resilience)

- “How do you ensure you get tasks done on time?” (Time management, reliability)

- “What do you do when you don’t understand something?” (Initiative, communication)

- “How did you cope with moving to a new country and adapting to a new culture?” (Adaptability, resilience, cultural awareness)

- How to Articulate: Use action verbs and provide concrete examples from their experiences. Instead of “I am a good communicator,” say “Effectively communicated needs and ideas in a diverse team setting to resolve project challenges.”

CV Structure and Content

A typical CV (Curriculum Vitae) should include:

- Contact Information: Name, phone number (local), email address, LinkedIn profile (if applicable).

- Personal Statement/Summary (Optional but Recommended): A brief, impactful paragraph highlighting key skills, experience, and career aspirations, tailored to the specific job.

- Work Experience: List in reverse chronological order. Include job title, company name, location, dates of employment, and 3-5 bullet points describing responsibilities and achievements (using action verbs). Crucially, help them frame informal work or experience from their home country in a professional context.

- Education: List highest degree/qualification first. Include institution name, location, dates of attendance. Mention any relevant courses or certifications.

- Skills: Divide into “Hard Skills” and “Soft Skills.” Also include language proficiency (with levels: basic, conversational, fluent, native).

- Volunteering/Projects (Optional): Relevant experience that demonstrates skills and commitment.

- References: Usually “Available upon request.”

Tips for CV Writing:

- Tailor: Emphasise tailoring the CV to each specific job application, matching keywords from the job description.

- Clarity and Conciseness: Use clear, simple language. Avoid jargon.

- Proofread: Stress the importance of meticulous proofreading for grammar and spelling.

- Format: Keep it clean, professional, and easy to read. One to two pages is ideal for entry-level or limited experience roles.

AI tools for effective CV writing

Introduction to AI Tools that can Assist in Writing Effective CVs

Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools are rapidly transforming job search strategies. While they should be used as assistants, not replacements for human input, they can significantly aid young people in crafting more effective applications.

How AI Tools Can Help:

- Grammar and Spelling Correction: Tools like Grammarly or built-in spell checkers in word processors can vastly improve the linguistic quality of written applications, especially for those whose first language is not the host countries’.

- Content and Keyword Optimisation:

- Resume/CV Builders with AI features: Many online platforms (e.g., Resume.io, Kickresume, Canva) offer AI-powered suggestions for wording, structure, and content based on job descriptions.

- Keyword Analysis Tools: Some tools (or even manually using a word cloud generator for job descriptions) can help identify frequently used keywords, which can then be incorporated into the CV to make it more ATS (Applicant Tracking System) friendly.

- Cover Letter Generation (with caution): AI writing assistants (like ChatGPT, Google Gemini, Microsoft Copilot) can generate draft cover letters based on a job description and the young person’s CV.

- Caution: Emphasise that these are drafts. They must be thoroughly reviewed, personalised, and fact-checked to ensure accuracy, authenticity, and a genuine voice. Over-reliance can lead to generic or even incorrect information.

- Skill Identification Prompts: AI can be prompted to suggest relevant hard and soft skills based on a job role or industry, helping young people brainstorm what they might include.

Practical Application with Young People:

- Explain the “Why”: Help them understand that AI is a tool to make their application stronger, not to do the work for them.

- Collaborative Approach: Work with them. Use AI as a brainstorming partner.

- Prompt Engineering (Simple): Teach them how to give clear instructions to AI. E.g., “Write a cover letter for a [Job Title] role at [Company Name]. My skills include [Skill 1], [Skill 2], and [Skill 3]. I am particularly interested in [Specific Aspect of Role/Company].”

- Review and Refine: Always review AI-generated content critically. Does it sound like them? Is it accurate? Does it truly represent their experiences and aspirations?

- Ethical Considerations: Discuss the importance of honesty and authenticity. AI should enhance, not fabricate.

Figure 9. Young person’s CV. Source: Pexels. Author: tima-miroshnichenko

Importance of Interview training

The Importance of Interview Training and Job Advertisement Analysis for Unaccompanied Refugee Minors

Unaccompanied refugee minors face unique challenges when they enter the labor market. Unlike many of their peers, they often lack parental support, professional networks, or prior experience with recruitment processes. This makes the transition into employment more difficult and increases the risk of exclusion. Providing these young people with training in job interview techniques and the analysis of job advertisements is therefore essential, not only to help them find work but also to support their wider integration and independence.

Interview training allows unaccompanied minors to build confidence, develop communication skills, and reduce the anxiety that often comes with speaking to potential employers. It teaches them how to present their strengths clearly and how to translate life experiences—such as resilience, adaptability, and problem-solving—into qualities that employers value. Similarly, training in job advertisement analysis equips them with the ability to understand what an employer is truly looking for. Many advertisements use technical or coded language, which can be difficult for young people unfamiliar with the job market to interpret. Learning how to identify essential qualifications, spot key skills, and recognize company values helps them prepare stronger applications and perform more effectively in interviews.

Beyond employability, these skills play an important role in integration. Gaining meaningful work gives refugee minors a sense of purpose, financial independence, and belonging within their host community. Most importantly, interview and job-advertisement training provides them with tools they can use throughout their lives, ensuring that they are not only prepared for one job application but for many opportunities to come.

Analysis of the work advertisement:

It’s actually one of the most important steps in both writing a tailored application (CV + cover letter) and preparing for interviews. Here’s why and how:

🔎 Why Analyze the Job Advertisement?

- Keywords & Skills

Employers usually list the exact skills, tools, and experiences they want. These are the keywords you should mirror in your CV and cover letter. - Responsibilities & Expectations

The ad tells you what the role involves day-to-day — you can prepare examples from your past experience that show you can do those tasks. - Company Culture & Values

Phrases like “fast-paced environment”, “collaborative team”, or “customer-first mindset” give clues about what kind of person they want to hire. This helps you adjust your tone and prepare behavioral interview answers.

📝 How to Use the Job Ad for Your Application

- CV → Highlight experience that matches the listed requirements. Place the most relevant skills and achievements at the top.

- Cover Letter → Directly address the job description: show enthusiasm for the role, mention the company’s mission/values, and explain why your background makes you a fit.

🎤 How to Use the Job Ad for Interview Prep

- Likely Questions: Each requirement in the ad can become a question. Example: if they ask for “project management skills”, expect something like: “Tell me about a time you managed a project from start to finish.”

- STAR Method: Prepare structured examples (Situation, Task, Action, Result) for each major skill mentioned.

- Questions for Them: Formulate smart questions about the role/company that show you’ve read the ad carefully.

Interview training

- Types of Interview Questions

Most interviews mix these categories:

- Introductory – “Tell me about yourself.”

- Motivation – “Why do you want this job / company?”

- Competency / Behavioral – “Tell me about a time when…”

- Technical / Role-specific – testing your skills or knowledge.

- Strengths & Weaknesses – “What’s your biggest strength?”

- Closing – “Do you have any questions for us?”

🔹 2. Answer Frameworks to Practice

- Tell Me About Yourself → Past → Present → Future

- Behavioral (e.g., teamwork, leadership, conflict) → STAR method:

- Situation – brief context

- Task – your role/responsibility

- Action – what you did

- Result – measurable or positive outcome

- Strengths → Back it up with an example.

- Weaknesses → Share a real but not critical weakness, and explain how you’re improving it.

🔹 3. Practical Training Exercises

- Mock Questions Practice – Answer out loud, not just in your head.

- Record Yourself – Video or audio; check for clarity, confidence, and body language.

- Time Management – Aim for 1–2 minutes per answer, not a long story.

- Prepare Questions for Them – Shows genuine interest.

🔹 4. Interview Etiquette

- Before: Research company, role, values.

- During: Smile, maintain eye contact, listen carefully, don’t rush.

- After: Thank them, and if possible, send a short follow-up email.

🔹 5. Common Interview Questions to Practice

- Tell me about yourself.

- Why do you want this role?

- What do you know about our company?

- What’s your biggest strength?

- What’s a weakness you’re working on?

- Tell me about a time you solved a problem.

- Tell me about a time you worked in a team.

- Where do you see yourself in 5 years?

- Why should we hire you?

- Do you have any questions for us?

✅ In short: Interview training + job ad analysis empower refugee minors to compete fairly, build confidence, understand expectations, and integrate into society through meaningful work.

Help Young People find work and become independent

Public Employment Services (PES)

PES are key resources. Each country has its own national PES, which often offer specialised services for young people, migrants, and job seekers with specific needs.

General Services Offered by PES:

- Job Matching: Databases of job vacancies.

- Counselling and Guidance: Career advice, vocational guidance, and individual action plans.

- Training and Upskilling: Information on vocational training, language courses, and professional development programs.

- Workshops: CV writing, interview skills, job search techniques.

- Labour Market Information: Statistics on employment, wages, and shortages.

- Financial Support: Information on unemployment benefits or training allowances (eligibility varies greatly).

Key National Public Employment Services:

As a professional, a key part of your role is to guide young people to the public employment services (PES) of their host country. These services are crucial for labour market integration, offering a range of support from job matching and vocational training to counselling and social security guidance.

The national public employment services of our partner countries are part of the European Network of Public Employment Services (PES Network). This network facilitates cooperation and the sharing of best practices across Europe, ensuring a high standard of service (European Commission, n.d.b). For a comprehensive overview of each country’s services, you can refer to the official PES Network website: https://employment-social-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies-and-activities/coordination-employment-and-social-policies/european-network-public-employment-services-pes-network_en

Here is a list of the key national PES for each country:

National Public Employment Services (Direct Links):

- Belgium (VDAB – Flanders): https://www.vdab.be/

- Belgium (Forem – Wallonia): https://www.forem.be/

- Belgium (Actiris – Brussels): https://www.actiris.brussels/

- Germany (Bundesagentur für Arbeit): https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/

- Spain (SEPE): https://www.sepe.es/

- Greece [DYPA (ΔΥΠΑ – Δημόσια Υπηρεσία Απασχόλησης). Formerly known as OAED]: https://www.dypa.gov.gr/

- Bulgaria (Employment Agency – AZA): https://www.az.government.bg/

- Norway (NAV): https://www.nav.no/

Relevant EU and National Level Guidance Frameworks

As a professional, understanding the broader policy and funding landscape can help you identify and access valuable resources for the young people you support. These frameworks are not just abstract policies; they are the foundation for the concrete support services available on the ground.

- Youth Guarantee: This is a highly relevant EU initiative aiming to ensure that all young people under 25 years (or under 30 in some cases), whether in employment, education, or training (NEETs), receive a good quality offer of employment, continued education, apprenticeship, or traineeship within four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education (European Commission, n.d.d). This is a vital tool for young migrants and refugees to transition into stable, productive lives.

- European Social Fund Plus (ESF+): The ESF+ is the EU’s main financial instrument for investing in people. It provides funding for projects that support employment, education, and social inclusion. Many national programs for the integration of migrants and refugees, including language training and vocational support, are funded by ESF+. Knowing about this fund can help you identify local projects that may benefit the young people you work with (European Commission, n.d.a).

- Erasmus+: While primarily known for student mobility, certain components of Erasmus+ can support vocational training, apprenticeships, and youth exchanges that enhance the employability of young people, including those from migrant and refugee backgrounds (European Commission, n.d.e).

- National Integration Policies: Each country has specific, nationally-defined integration policies for migrants and refugees. These policies often include dedicated programs for language training, skills validation, and labour market integration. Familiarising yourself with these country-specific frameworks is essential for providing effective guidance.

- National Qualification Frameworks (NQFs): These frameworks are crucial for helping you understand and compare qualifications gained in different countries. They provide a standardised way to recognise prior learning and experience of young migrants, which is a key step towards formal employment or further education (Cedefop, n.d.b).

Strategies for Professionals

🧰 Strategy | ⚙️ Description / Practical Actions | 🌱 Goal / Impact |

|---|---|---|

Direct Referrals | Refer young people to National Public Employment Services (PES) and programs under ESF+ or Youth Guarantee | ✅ Ensures access to funded employment and education opportunities |

Accompanying Support | Join initial PES appointments or assist with online registration to overcome barriers | ✅ Builds confidence and ensures successful registration |

Information Hub | Keep updated info on local training, job fairs, and employer initiatives (especially EU-funded) | ✅ Improves access to relevant, current opportunities |

Networking | Partner with local employers, NGOs, and vocational programs to create pathways for URMs | ✅ Expands opportunities and advocacy channels |

Language Support | Facilitate access to job-search-related language programs | ✅ Improves employability and workplace integration |

Long-Term Planning | Help youth plan realistic career paths based on skills and available programs | ✅ Promotes sustainable employment and self-reliance |

Your role as professionals in migrant welcoming centres is indispensable. By applying the knowledge gained from this module, you are not merely assisting in job searches; you are empowering young individuals to build new lives, contribute to their new societies, and achieve sustainable independence with dignity and safety. Continue to be their advocates, their guides, and their support in navigating this challenging but ultimately rewarding path.

Case Assignment: Organizing a Job Fair for Unaccompanied Refugee Minors

References & further reading

References:

Here is a list of interesting links to further enhance your understanding of the labour market and programs for migrants in the specified countries. Please note: Websites and documents are subject to change and may be updated regularly. Always seek the most current information.

Actiris. (n.d.). Citizens. https://www.actiris.brussels/en/citizens/

Asylum Information Database. (n.d.a). Access to the labour market – Belgium. European Council on Refugees and Exiles.https://asylumineurope.org/reports/country/belgium/content-international-protection/employment-and-education/access-labour-market/

Asylum Information Database. (n.d.b). Access to the labour market – Spain. European Council on Refugees and Exiles. https://asylumineurope.org/reports/country/spain/reception-conditions/employment-and-education/access-labour-market/

Asylum Information Database. (n.d.c). Legal representation of unaccompanied children – Spain. European Council on Refugees and Exiles. https://asylumineurope.org/reports/country/spain/asylum-procedure/guarantees-vulnerable-groups/legal-representation-unaccompanied-children/

Bundesagentur für Arbeit. (n.d.). Living, studying, working in Germany. https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/en/

CEDEFOP. (n.d.a). Belgium. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/countries/belgium

Coface. (n.d.). Bulgaria: Country File, Economic Risk Analysis. https://www.coface.com/news-economy-and-insights/business-risk-dashboard/country-risk-files/bulgaria

Cedefop. (n.d.b). National qualification frameworks. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/tools/nqf

Enterprise Greece. (n.d.). Why Invest in Greece. https://www.enterprisegreece.gov.gr/en/greece-today-en/why-greece-en

EURES. (n.d.b). Labour Market Information: Bulgaria. European Union. https://eures.europa.eu/living-and-working/labour-market-information-europe/labour-market-information-bulgaria_en

European Commission. (n.d.a). European Social Fund Plus (ESF+). https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1081

European Commission. (n.d.b). European Network of Public Employment Services – PES Network. https://employment-social-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies-and-activities/coordination-employment-and-social-policies/european-network-public-employment-services-pes-network_en

European Commission. (n.d.d). Youth Guarantee. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1079&langId=en

European Commission. (2023a). In-Depth Review 2023 Greece – Economy and Finance. https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/document/download/16a894b0-490a-4052-9b23-70965df36636_en?filename=ip211_en.pdf

European Commission. (2025, January 20). REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION on the progress made in the European Union in combating trafficking in human beings. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52025DC0008

European Commission. (2024b). Economic forecast for Belgium. Economy and Finance. https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/economic-surveillance-eu-economies/belgium/economic-forecast-belgium_en

European Commission. (2024c). Economic forecast for Germany. Economy and Finance. https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/economic-surveillance-eu-economies/germany/economic-forecast-germany_en

European Commission. (2024e). Economic forecast for Spain. Economy and Finance. https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/economic-surveillance-eu-economies/spain/economic-forecast-spain_en

European Commission. (2023a). In-Depth Review 2023 Greece – Economy and Finance. https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/document/download/16a894b0-490a-4052-9b23-70965df36636_en?filename=ip211_en.pdf

European Parliament. (2013, June 26). Directive 2013/33/EU on standards for the reception of applicants for international protection. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32013L0033

FRA (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights). (n.d.). Protecting migrant workers from exploitation – FRA Opinions. https://fra.europa.eu/en/content/protecting-migrant-workers-exploitation-fra-opinions

GTAI (Germany Trade & Invest). (n.d.). Industries in Germany. https://www.gtai.de/en/invest/industries

Group Working. (2025, March 31). Popular professions in Germany 2025 – who are employers looking for. https://blog.group-working.com/en/professions-demand-germany-2025/

Guy-Evans, O. (2025, May 06). Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. Simply Psychology.

https://www.simplypsychology.org/bronfenbrenner.html

ILO (International Labour Organization). (n.d.a). What is child labour? https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/child-labour/lang–en/index.htm

ILO (International Labour Organization). (n.d.b). C182 – Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182). https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C182

International Trade Administration. (n.d.). Norway – Market Overview. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/norway-market-overview

Statistics Norway. (2023). Norway’s economy and social conditions. https://www.ssb.no/en/

Ministry of Migration and Asylum. (n.d.). Unaccompanied minors. https://migration.gov.gr/en/gas/diadikasia-asyloy/asynodeytoi-anilikoi/

NAV. (n.d.a). What is Nav?. https://www.nav.no/hva-er-nav/en

NAV. (n.d.b). Financial assistance. https://www.nav.no/okonomisk-sosialhjelp/en

OHCHR. (n.d.). Submission by the Republic of Bulgaria to OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Migration/CallEndingImmigrationDetentionChildren/Member_States/Republic_of_Bulgaria_submission.docx

Skatteetaten. (n.d.). Income from employment for children under the age of 13. https://www.skatteetaten.no/en/person/taxes/tax-deduction-card-and-advance-tax/employment-income-for-children-under-13/

UNHCR. (n.d.). Applying for asylum in Bulgaria. https://help.unhcr.org/bulgaria/applying-for-asylum-in-bulgaria/

Zoll.de. (n.d.). Protection of young people at work. https://www.zoll.de/EN/Businesses/Work/Foreign-domiciled-employers-posting/Minimum-conditions-of-employment/General-conditions-of-employment/Protection-of-young-people-at-work/protection-of-young-people-at-work_node.html

UNHCR (2025). The Unbreakable Promise: Resilience and Resolve in Refugee Education. Refugee Education Report. UNHCR Education Report 2025 | UNHCR

UNHCR (2024). Global Trends Report. https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2024

UNICEF (2023). The education response for Syrian children under Temporary Protection in Türkiye. https://www.unicef.org/turkiye/media/15931/file/The%20education%20response%20for%20Syrian%20children%20under%20temporary%20protection%20in%20Türkiye%20report.pdf

UNICEF (2022). Inclusion of Syrian refugee children into the national education system – Turkey. Case Study. https://www.unicef.org/media/111666/file/Inclusion%20of%20Syrian%20refugee%20children%20into%20the%20national%20education%20system%20-%20Turkey.pdf

UNESCO & UNHCR (2022). Paving Pathways for Refugee Inclusion: Jordan Case Study. Paving pathways for refugee inclusion: Jordan case study | UNESCO

UNESCO & UNHCR (2022). Paving Pathways for Refugee Inclusion: Colombia Case Study. https://www.unesco.org/en/emergencies/education/data/refugees/colombia

World Bank & UNHCR (2021). The Cost of Inclusive Refugee Education. The Global Cost of Inclusive Refugee Education. | UNHCR

UNHCR (2024). An Overview of the Evidence on the Effects of Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) on Forcibly Displaced Children. An overview of the evidence on the effects of social and emotional learning (SEL) on learning and well-being of forcibly displaced children | UNHCR

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) (2021). Global education indicators and refugee enrolment data. UNESCO UIS

UNICEF (n.d.). Psychosocial support and education in emergencies. Education in emergencies | UNICEF